A True and Perfect Viking: The Search for the Real Hasting

Separating ninth-century history from 19th-century myths.

Some years ago, I had the delight of reading Thomas Asbridge’s The Greatest Knight: The Remarkable Life of William Marshal. I found myself captivated by his use of the phrase “a true and perfect knight,” a term he borrowed from the sixteenth-century writer George Peele to frame Marshal as the epitome of medieval chivalry. Yet, as I read, a question lingered in my mind: Could such a title be assigned to a Viking? And if so, who might that Viking be?

The notion seemed paradoxical at first. After all, the Vikings have been historically branded as ruthless raiders, pirates, and invaders, which is a far cry from the romanticized ideals of chivalric knighthood. But as modern scholarship has revealed, the Vikings were far more complex: explorers, traders, cunning tacticians, and culture-shapers whose influence rippled across Europe and beyond. It seemed to me that finding a “true and perfect Viking,” or one who exemplified their ferocity as much as their adaptability, leadership, and mystery of the Viking Age, could offer profound insights into the Vikings’ historical role and how we perceive them today.

This question led me to Hasting, a ninth-century figure who looms large in the sources of his day but is equally shrouded in myth and misunderstanding. Much like the Vikings as a whole, Hasting’s story is one of duality: on the one hand, he was a cunning raider and leader who shaped his time, appearing at regular intervals in the sources; on the other, his historical narrative has been inflated, distorted, and transformed into legend by professional and amateur historians alike. In Hasting, I saw not just the perfect candidate for my search but also a reflection of the controversies and mysteries that have come to define the study of the so-called Viking Age.

As a writer of historical fiction, I must acknowledge that I play no small part in the mythmaking surrounding Hasting. Through my novels, I have sought to bring him to life for modern readers, weaving together his exploits from the sparse sources that mention him while filling in the gaps with creative license. Yet, even as I strive to remain faithful to the sources, there lies the rub: the dearth of records on Hasting, particularly before the year 850, affords me—and indeed, anyone who attempts to tell his story—a near-blank canvas for his early life. This creative freedom has allowed me to construct a vivid narrative for him, but also underscores our challenges when grappling with his historical legacy. The lack of concrete evidence has invited mythmaking over the centuries and highlights the broader complexities of reconstructing the Viking Age from the fragmentary evidence available.

The broader study of the Viking Age is deeply entangled with the myths and legends that emerged long after the era. Much of what we associate with the Vikings today—horned helmets, unbridled savagery, and a homogeneous warrior culture—can be traced back to the nineteenth century. This period, characterized by rising European nationalism, saw the Vikings appropriated as symbols of strength, exploration, and cultural purity. Scandinavian countries, in particular, leaned heavily into Viking imagery to assert their historical significance. Romanticized sagas, grandiose art, and even historical reinterpretations painted the Vikings as larger-than-life figures, embodying traits that spoke more to the nineteenth century’s aspirations than the actual Norse people.

In recent decades, however, historians and archaeologists have worked to peel back these layers of myth. The shift in scholarship toward skepticism and critical analysis of inherited narratives has been transformative, fundamentally altering our understanding of the Norse world. A renewed focus on tangible evidence, including archaeological finds, environmental studies, and material culture, enables historians to reconstruct a more accurate picture of daily life and activities. Excavations of sites such as Jorvic, Ribe, and Hedeby have shed light on the Vikings’ urban sophistication and craftsmanship. Advances in archaeological techniques, such as isotope analysis and DNA studies, have provided unprecedented insight into the Viking Age, revealing a far more nuanced and interconnected world. Trade goods and coin analyses illustrate their engagement with economies spanning the Middle East to the British Isles; far from being isolated plunderers, the Vikings were integral participants in a vast trade network.

When we focus on Hasting, we find a figure whose activities epitomize the “ideal” Viking, embodying the traits of ambition, audacity, and cunning that defined the Norse in their time. His bold raids, plundering expeditions, and enduring impact on the Carolingian Empire established him as a significant figure of the Viking Age. The intense scorn he receives in later chronicles, such as Dudo of Saint-Quentin’s Gesta Normannorum, where the author uses no fewer than fifty expletives to describe him, underscores the scale of his activities and the damage he inflicted. His Vilification, written more than a century after his exploits, reflects the lasting impression Hasting made on his contemporaries and the subsequent generations who chronicled him. Hasting also engaged in diplomacy and political strategy, brokered peace between enemies when it suited his goals, allied himself with factions to gain advantage, and exploited rivalries to further his enrichment and survival. His ability to navigate the fractured political landscape of the Carolingian world demonstrates a level of strategic thinking that transcended the simple stereotype of the Viking raider.

Hasting’s legacy, however, is not without controversy. He has been credited with many deeds and events for which there is no direct evidence linking him. Such a lack of clarity and the scarcity of early sources have made him a figure of fascination and debate. While his prolific activities are attested to by the sheer number of hostile mentions, the gaps in the historical record have allowed later writers to construct a certain mythology around him. His enduring reputation as a ruthless raider and cunning strategist reflects this interplay between historical fact and later mythmaking.

Historians have speculated on Hasting’s presence at the battle of Noirmoutier in 836, where Franks clashed with Viking forces, and at the death of the chieftain Horic in 838, which reportedly left a power vacuum among the Norse. He has also been linked to the infamous sack of Nantes in 843, where the city was brutally plundered, and to the legendary siege of Paris in 845, where the semilegendary Ragnar Lothbrok’s forces allegedly laid waste to the Carolingian capital. These associations demonstrate the tendency toward conjecture that has plagued this field for over a century.

Hasting’s story highlights how conjecture and myth have often filled the gaps left by a sparse and fragmented historical record. The absence of definitive evidence has magnified and distorted his legacy, transforming him into a figure who is as much a product of later interpretation as he is of his own time. Through this process, Hasting has come to symbolize the broader difficulties of studying the Vikings.

In the following article, we will explore both sides of Hasting’s legacy, first with a review of the mythmaking done by 19th and 20th century historians, focusing on the works of Michel Dillange, and then reviewing all the source material (of which there is not very much) for Hasting’s life to demonstrate the gulf between what historians have popularized and what we actually know about the man.

Hasting is the central character in my award-winning, bestselling historical fiction series The Saga of Hasting the Avenger, pictured below (click the image to shop my books).

The Modern Myth of Hasting

Hasting occupies a peculiar place in the popular and scholarly memory of the Viking Age. While figures like Bjorn Ironside, Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, Ivar the Boneless, and Ubbe—the supposed sons of Ragnar Lothbrok—have been widely analyzed and celebrated in the anglophone world, Hasting has not enjoyed the same level of attention. The disparity may be attributed to the geographic focus of his exploits. Unlike his contemporaries, who are remembered for their campaigns in England, Hasting directed much of his energy toward the Frankish Empire and Brittany, conducting raids, brokering alliances, and navigating the fractured political landscape of what is modern-day France and its surrounding regions. Consequently, his story has resonated more profoundly in the francophone world, where historians and storytellers have built his legend.

In any serious attempt to reconstruct the life of Hasting, one quickly encounters a tangle of half-remembered raids, fragmented chronicles, and centuries of mythmaking. Few Viking figures have had their legacies so aggressively expanded by later writers, and few accounts illustrate this better than the one found in Michel Dillange’s Les Comtes de Poitou: Ducs d’Aquitaine (778–1204), which, unfortunately, continues to be cited by mainstream historians. Dillange presents a sweeping and vivid portrait of Hasting as a relentless force of nature, orchestrating nearly every major raid and military encounter along the Loire and beyond during the mid-ninth century. Hasting’s chapter, drawn from the long-standing French historiographical tradition, offers perhaps the most ambitious narrative synthesis of his life ever written.

Dillange’s portrayal of Hasting is valuable because it shows how legend and scholarship have often intertwined. Dillange’s text serves as a kind of modern saga that stitches together fragmentary sources into a cohesive story of a single figure whose actions defined a generation of violence. Rather than framing Hasting as one among many raiders, Dillange elevates him as the principal agent behind decades of destruction in Western France and the surrounding regions.

Dillange briefly recounts Raoul Glaber’s claim that Hasting was born near Troyes in northeastern Francia, suggesting he may have been the child of Saxon deportees resettled by Charlemagne. Dillange treats this hypothesis as plausible, framing Hasting’s origins as a journey from outsider to self-fashioned Scandinavian, beginning in the ports of Frisia, perhaps Dorestad, where he supposedly met Danish sailors and followed them north. From there, Dillange imagines him starting as a trader, then transforming into a pirate and eventually a feared military leader.

The first clear military event Dillange attributes to Hasting is his participation in the assault on Noirmoutier in the mid-830s. He places Hasting as a member of the Viking force that repeatedly attacked the island, eventually sacking the abbey of Saint-Philbert and forcing the monks to relocate to Déas. According to Dillange, Hasting rose to command following the death of his chieftain, Horic, in 838, and from that point forward, led operations up the Loire. Dillange states that it was Hasting who seized Amboise and later appeared in Normandy at Jumièges and Rouen in 841.

Dillange then traces Hasting’s alliance with Breton and Frankish defectors. In 841, Hasting is said to have joined Lambert of Nantes and Nominoë of Brittany in opposition to Charles the Bald. Together, they defeated Count Renaud of Nantes at Blain. In the aftermath, Dillange writes, Hasting entered the city of Nantes on Saint John’s Day and murdered the Bishop Gohard on the cathedral steps—an event that marks one of the most notorious moments in the Carolingian memory of Viking violence.

The chronology continues with Hasting’s raids up the Loire Valley, including attacks on Angers, Saumur, and Chinon. Dillange claims that Hasting attempted to take Tours but withdrew after assessing the city’s strong defenses. He then returned to Denmark to recruit more forces, where he attended a thing presided over by King Horic the Younger. From this assembly, Dillange says, Hasting returned with reinforcements and allied himself with Bjorn Ironside.

With this new force, Dillange credits Hasting with devastating the Garonne valley and much of Aquitaine from 848 to 849. He describes a long list of cities plundered—Bordeaux, Saintes, Angoulême, Melle, and many others. These campaigns, Dillange argues, were carried out with near impunity due to the inability of the Frankish crown to mount a coherent military response.

Dillange continues by narrating Hasting’s Mediterranean expedition, including the supposed sack of Luna using the infamous “dead man’s ruse,” in which Hasting faked his death to gain access to the city and lead a surprise attack. The narrative from here becomes increasingly expansive. Dillange’s Hasting burns his way through northern Spain, Portugal, Southern France, and Tuscany, even venturing up the Rhône to Arles and beyond. Dillange acknowledges that some of these accounts may be embellished, but he repeats them nonetheless, treating them as plausible, given Hasting’s supposed reputation and ambition.

In the later 850s and early 860s, Dillange attributes to Hasting the establishment of fortified bases on the Loire, notably at Saint-Florent-le-Vieil. He is said to have attacked Orléans, Blois, Poitiers, and Fleury and suffered a rare defeat at Poitiers in 856. Nevertheless, Dillange casts Hasting as a resilient figure, able to recover and resume raiding. He also ties Hasting to political maneuvering, stating that he helped install Lambert as count in Nantes and cooperated at times with Pepin II of Aquitaine.

By the late 860s, Dillange paints Hasting as a figure seeking stability. He writes that he accepted the county of Chartres in 882, granted by King Carloman II. But the lure of adventure and the Viking world proves too strong. In 886, Dillange claims, Hasting sells his title to fund a final campaign to England, after which he disappears from the historical record.

Michel Dillange’s narrative of Hasting is rich and engaging, but it veers frequently into speculation presented as fact. While some of the events he describes did occur, the evidence tying Hasting to them is often tenuous or nonexistent. His portrayal of Hasting as a central figure in nearly every major Viking action in western Francia from the 830s to the 860s reflects an outdated tendency in French historiography to attribute almost every act of Scandinavian aggression in the region to a single named individual, typically Hasting. However, a critical review of the sources reveals how much of this account rests on conjecture.

First, Raoul Glaber’s 11th-century history, which Dillange cites for Hasting’s early life, allegedly used older documents that did not survive to today to synthesize its narrative. Glaber’s history is full of questionable inclusions and has, in recent times, been almost entirely dismissed for its outright fabrications. Therefore, the premise for Hasting’s early life as a displaced Saxon who then returned north to become a Viking appears to be a fiction (discussed in more detail below), barring new evidence to corroborate Glaber’s assertions.

Further, no contemporary evidence places Hasting at the sack of Noirmoutier in 834 or 836 or at the battles against Count Renaud. The only definitive Viking attack on Noirmoutier mentioned in early sources before 843 is Alcuin's in 799, and later a royal charter issued by Louis in 819. No Viking leader is named until 843. The connection of Hasting to the occupation of Noirmoutier is entirely speculative and likely based on later attempts to retroactively organize the chaotic records of early Viking raids under prominent names.

Dillange places Hasting at the Battle of Blain in 843, where Count Renaud was allegedly ambushed and killed. However, no primary source from the period names Hasting in this context. The attribution stems from conflating later chronicles with earlier events, likely inspired by the presence of a Viking force, but Hasting himself is not clearly identified.

The claim that Hasting took part in the sack of Nantes in 843 and killed Bishop Gohard on the altar is perhaps the most repeated and least substantiated story. The attack is well documented, but the Annals of Saint-Bertin and the Annals of Angoulême do not name the Viking leader. The only mention of Hasting’s presence at the sack of Nantes is the Chronique de Nantes, which has long been debunked as a later fabrication.

Dillange goes further by claiming that Hasting launched attacks on Angers, Saumur, Chinon, Tours, and various towns along the Loire, Gironde, and even inland to Périgueux and Montauban—essentially attributing every raid in the region between 843 and 860 to him. The problem is that many of these raids were carried out by different bands, often unconnected and not under a unified command. Viking expeditions were largely independent enterprises. Only a few major campaigns—like that of 866 in England—display the central coordination Dillange implies.

The legend of Luna, involving the ruse of Hasting feigning death to enter the city, appears in later saga literature and was popularized by Dudo. It has no contemporary basis. The Mediterranean expedition attributed to Hasting, including attacks on Pisa and Barcelona, among others, relies entirely on later, often contradictory, narratives with no support in ninth-century Frankish or Arab sources.

Finally, Hasting’s appointment as count of Chartres in 882 is documented, but even this comes long after the events Dillange claims. There is no clear continuity between the supposed Loire warlord of the 830s–850s and the later Hasting. The gap in documentation is wide enough that some scholars suggest the possibility of two different men named Hasting.

In sum, Dillange’s biography confuses legend with fact and stitches together scattered events to create a singular heroic-villain narrative that the sources do not support. While it makes for compelling storytelling, it falls short of modern standards of historical rigor. Michel Dillange is not alone in propagating this narrative of Hasting, and for good reason—it puts a face to the terror of the Vikings and creates a cohesive story of one of the most feared leaders of the Viking Age. Hasting’s exploits, as recounted here, provide an evocative and dramatic account of Viking activity in the ninth century, shaping our understanding of their role in the Frankish world. However, despite the vivid storytelling and the compelling image of Hasting as the quintessential Viking chieftain, primary sources do not corroborate much of this narrative. Hasting cannot be definitively confirmed as the leader of many war bands or the architect of events attributed to him in Dillange’s work.

Still, Dillange’s synthesis and school of thought remain broadly popular, as is the case with many aspects of the so-called “Viking Age.”

The Real Hasting

When it comes to figures of the Viking Age, we can broadly classify them into three categories: legendary, semilegendary, and historical. The key distinction between these categories lies in the types of sources in which their stories are preserved. Legendary figures, such as Ragnar Lothbrok, belong to the realm of nonhistorical saga literature—works like Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla or the Poetic Edda in the Codex Regius. These sources are steeped in myth, often blending fantastical elements with kernels of historical memory, making it impossible to separate fact from fiction.

Semilegendary figures, like Bjorn Ironside or Ivar the Boneless, occupy a middle ground. Their exploits are documented in both sagas and semicontemporary histories, such as Saxo Grammaticus's Gesta Danorum and medieval chronicles written a century or two after their purported lifetimes. Though closer to the events they describe, these accounts remain deeply influenced by oral tradition and creative storytelling.

The third category, historical figures, is defined by the presence of contemporary accounts written during or immediately following the Viking Age. Though often terse and biased, these sources provide a much firmer foundation for understanding the lives and deeds of their subjects. Figures like Harald Hardrada and Alfred the Great fall firmly into this category, with their actions documented in works such as the Morkinskinna and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, respectively. However, even among historical figures, the level of detail and reliability varies significantly, depending on the surviving evidence.

Hasting presents an interesting case. Unlike many Viking figures, whose lives are shrouded in legend or reconstructed from scant sources, he is mentioned in contemporary sources, albeit sparingly. He does not belong entirely to the realm of legend, nor is he as well-documented as figures like Alfred or Harald. Instead, Hasting straddles the line between history and myth, with contemporary texts such as the Chronicon of Regino of Prüm and the Annals of Saint-Vaast shedding light on his actions. These accounts are further supported by corroboration in the Annals of Saint-Bertin, lending credibility to at least some of the events attributed to him. Notably, Hasting also appears in semicontemporary sources alongside figures like Bjorn Ironside, occupying a unique space where history and storytelling converge.

We will focus here on the real Hasting, as revealed by these contemporary sources. While his presence in these records marks him as a historical figure, the brevity of these accounts leaves much to the imagination. As we have seen, later chroniclers and modern historians have filled this ambiguity with speculation and narrative. By setting a firm foundation for what can be verified, we aim to separate the man from the myth and uncover the historical Hasting.

Raoul Glaber’s Histoires

Raoul Glaber’s account of Hasting offers the closest thing we have to a source on the Viking leader’s early life. Writing in the eleventh century, more than a century after Hasting’s exploits, Glaber crafted a narrative of humble beginnings, meteoric rise, and devastating impact. His version is tantalizing in its specificity: Hasting, or Astingus, was allegedly born in a small village near Troyes, the son of peasants, and rejected his lowly origins to pursue power through a life of piracy. According to Glaber, Hasting’s charisma and cunning earned him leadership among the Normans, and his campaigns left an indelible mark on the Frankish Empire.

The passage about Hasting is found in Book 1, Chapter 5 of Les cinq livres de ses histoires (900-1044), written by Raoul Glaber, edited by Maurice Prou, and published in 1886 by A. Picard in Paris. I have translated the text from Latin here:

“During this period, the Gaulish peoples suffered no lesser calamity from the incursions of the Normans. These Normans derived their name from their origin, as they first departed boldly from the northern regions, driven by a love of plunder, and sought the western lands. Indeed, in their own language, “Nort” means north, and their people are thus called Nortmanni, meaning “men of the north.”

At first, during their early raids, they dwelt near the ocean for a long time, satisfied with small tributes. Over time, however, they grew into a considerable force, uniting into a significant nation. Eventually, with powerful armies by land and sea, they traversed territories, claiming several cities and provinces for themselves.

In the course of time, there arose a certain man in the region of Troyes, of the lowliest peasant origin, named Hasting (Astingus), from the village called Tranquillus, three miles from the city. This man, though young and strong in body, was of a corrupt and wicked disposition. Disdaining the poor fortune of his humble parents and consumed with the desire to rule, he chose exile over servitude. Secretly leaving his home, he attached himself first to the aforementioned Normans.

Serving them through continual acts of plunder, Hasting provided sustenance for others, who collectively called themselves a fleet. While serving for a time under this wicked custom, he became more diligent as a result of his increasingly nefarious actions. Gradually becoming stronger than his comrades in both physical strength and resources, they all unanimously appointed him as their leader by land and sea.

Once appointed, he embraced even greater cruelty. Disregarding the savagery of the past, he began extending his sword into distant provinces. Later, with nearly his entire following, he embarked on a campaign into the northern parts of Gaul. Though a destructive leader, he sought to revisit his native land, albeit with wicked intent.

When he arrived, he laid waste to everything with sword and fire, surpassing any prior destruction, as no one resisted him. He spent a long time ravaging the region. At that time, nearly all the churches throughout Gaul, except for those in fortified towns or castles, were desecrated and burned. After traversing all of Gaul and seizing rich spoils of all kinds, he led his army back to his base.

Thus, in the nearly one hundred years that followed, such calamities were inflicted upon the people of Gaul far and wide, both by Hasting himself and by the leaders of his people who succeeded him.”

Glaber’s narrative aligns with Michel Dillange’s theory that Saxons or Danes from Saxony, resettled into the Frankish Empire by Charlemagne for conversion, might have contributed to Hasting’s origins. Glaber’s claim that Hasting abandoned his family to rediscover his roots in the north, ultimately joining Viking raiders, aligns with this hypothesis. It is, on the surface, plausible: Hasting’s rise to prominence could conceivably have begun in the displacement and cultural tensions of Charlemagne’s empire. This convergence of accounts from Glaber and Dillange creates a narrative consistency that tempts the historian to accept it as fact.

But this plausibility should give us pause. While it lends credibility to Glaber’s narrative, it also highlights how fragile our understanding of Hasting’s early life is. The absence of corroborating evidence in accurate contemporary sources exposes us dangerously to conjecture. Did Hasting emerge from the village of Tranquillus, three miles from Troyes? Was he truly a Saxon-descended Frank who returned to his Scandinavian roots, or is this merely a moralistic tale reflecting the fears and biases of the eleventh-century Frankish Church? Without additional evidence, we cannot know.

What Glaber provides, then, is not so much a biography as a reflection of the anxieties of his time. By framing Hasting as a peasant-turned-pirate who wreaked havoc on the Frankish Empire, Glaber transforms him into a figure of cautionary legend. This version of Hasting’s story demonstrates how history and myth become entangled, offering insights into the narratives medieval chroniclers crafted to explain their world. It also sets the stage for us to peel back the layers of myth and conjecture to reveal, as best we can, the historical Hasting beneath.

The value of Glaber’s account in the discussion of Hasting lies not necessarily in its factual accuracy, but in the fact that Hasting is remembered at all. For an eleventh-century chronicler to evoke Hasting’s memory decades after his time speaks to the enduring impression he made on the Frankish world. Whether Glaber’s origin story proves true or not, it reflects how Hasting was perceived—an infamous figure worthy of narrative embellishment and moral caution. Were this the only source on him, he would comfortably fit within the semilegendary category—a figure whose life is more conjecture than fact, molded by the hands of chroniclers like Glaber. However, we are fortunate to have additional sources that shed further light on his exploits.

Gesta Normannorum

The Gesta Normannorum (Deeds of the Normans) by Dudo of Saint-Quentin is another semicontemporary source that merits attention in exploring Hasting’s historical presence. Written between 996 and 1015 CE, the work was commissioned by Richard I of Normandy and later supported by his successor, Richard II. Dudo, a Norman courtier and cleric, set out to provide a history that celebrated and legitimized the Norman rulers, tracing their lineage and triumphs from their Scandinavian origins to their consolidation of power in northern France.

Though the Gesta Normannorum was written more than a century after the peak of Hasting’s exploits, it occupies a pivotal position in the historical tradition. Like Raoul Glaber’s Histoires, Dudo’s work blends historical events with rhetorical flourishes to glorify Norman heritage. The narrative is rife with dramatic depictions of Viking valor and cunning, positioning figures like Rollo—the founder of Normandy—as almost mythical ancestors of the Norman dukes. While Hasting does not dominate the Gesta Normannorum in the same way as Rollo or other Norman forebears, his inclusion signals his enduring notoriety and the impact of his deeds on the collective memory of the time.

As with Glaber, Dudo’s account of Hasting raises questions about the veracity of its claims. The passage of time between Hasting’s lifetime and Dudo’s writing allows room for embellishment and error. However, the fact that Dudo felt it important to mention Hasting alongside the formative figures of Norman identity reinforces the idea that Hasting’s deeds, whether accurate or not, had become part of the narrative fabric that shaped the Norman understanding of their Scandinavian roots.

Dudo relays to us the following:

“So much does this accursed and headstrong, extremely cruel and harsh, destructive, troublesome, wild, ferocious, infamous, destructive and inconstant, brash, conceited and lawless, death-dealing, rude, everywhere on guard, rebellious traitor and kindler of evil, this double-faced hypocrite and ungodly, arrogant, seductive and foolhardy deceiver, this lewd, unbridled, contentious rascal… aggravate towards the starry height of heaven an increase of destructive evil… that he ought to be marked not by ink but by charcoal.”

The laundry list of insults serves a rhetorical purpose: to paint Hasting as an agent of divine punishment, a scourge sent by God to chastise a corrupt Frankish realm. This demonization is typical of Christian sources describing pagan leaders, especially those who attacked monasteries. While this kind of language reveals little about Hasting’s actual character, it tells us much about how Frankish authors processed the trauma of Viking raids. Hasting is imagined here less as a man and more as a symbol of chaos.

“Then Anstign has jumped down from the bier and snatched his flashing sword from its sheath. The calamity-causing one has attacked the prelate… He is slaughtering the prelate and, having overthrown the count, the clergy standing defenseless in the church as well… The frenzy of the pagans butchers the defenseless Christians… Anstign would boast with his followers, supposing that they have captured Rome, the head of the world.”

This passage recounts the infamous ruse in which Hasting, feigning death and having requested a Christian burial, is carried inside a fortified city, identified as Luna in Tuscany, and springs back to life mid-funeral to lead a massacre. It’s one of the most enduring and colorful tales associated with Hasting, found in several medieval chronicles, including Dudo of Saint-Quentin and the Chronicon of Geoffrey of Cambrai. The detail about mistaking Luna for Rome adds an ironic flourish, underscoring the chronicler’s view of the Vikings as simultaneously cunning and ignorant barbarians. While it makes for dramatic storytelling, modern historians widely consider this episode apocryphal. It serves as a morality tale about pagan deception and Christian gullibility rather than as a reliable historical account.

“Peace-making ambassadors are directed to harsh Anstign… He is not rejecting the peace which was being requested but, of his own accord, is giving it for a longer time! Thus, once an unshattered peace between the chiefs has been secured… they are made, of one mind, united.”

This excerpt refers to Hasting’s (Anstign’s) diplomatic dealings with the Frankish court, allegedly resulting in a four-year peace treaty. Such events reflect a common strategy among Carolingian rulers: using tribute (or Danegeld) and negotiated settlements to pacify Viking threats when military resistance was impractical or too costly. That Hasting is portrayed as agreeing to peace “of his own accord” may be an attempt to soften the blow to Frankish pride, framing the agreement not as submission but as an arrangement with a sovereign equal. While the narrative here lacks nuance, it aligns with historical trends: Hasting eventually entered the service of Frankish kings and was granted land, as confirmed by later sources. However, this peace should be read as a pragmatic move in a chaotic time, not a moral reconciliation between worlds.

Dudo’s account, while rich in vivid detail and moral condemnation, ultimately tells us more about the fears and fantasies of the Franks than it does about the real Hasting. Though the intensity of Dudo’s portrayal suggests that Hasting’s name carried significant weight in the Frankish and later Norman imaginations, his narrative is better understood as mythmaking than reliable history. Rather than offering factual insight, Dudo’s depiction elevates Hasting into a semilegendary figure whose exaggerated exploits served as a vehicle for moral lessons and cultural anxieties rather than a faithful reconstruction of events.

Regino of Prüm

Of all early medieval sources that reference Hasting by name, Regino of Prüm offers the most vivid, detailed, and sustained accounts of his activity. Writing from the monastic center of Prüm in the late ninth century, Regino preserves a glimpse of the Viking campaigns along the Loire that not only names Hasting but characterizes him as a formidable and cunning leader. His narrative provides key insights into how Viking warbands operated in Francia and how Hasting’s reputation elevated him beyond that of a typical raider.

The entry for 867 is the earliest secure identification of Hasting in Regino’s Chronicon. It recounts a dramatic encounter near the Loire, where Hasting and his men, having ravaged Nantes, Angers, Poitiers, and Tours, are caught by surprise by the Frankish commanders Robert the Strong and Ranulf of Aquitaine. Realizing they cannot retreat to their ships, the Northmen fortify themselves inside a large stone church in a nearby village. Regino explicitly names Hasting as their leader. What follows is a tightly narrated siege in which the Northmen are initially pinned down, only to launch a surprise sortie. In the ensuing chaos, Robert is slain, Ranulf is mortally wounded, and the Frankish army falls apart. Hasting emerges not only victorious, but also as a tactician capable of exploiting lapses in enemy discipline.

This incident reveals much about the operational methods of Viking bands and Hasting’s personal leadership. The Northmen’s choice to occupy a fortified church is emblematic of their increasing use of local infrastructure to resist counterattacks. The sudden reversal of the siege—resulting in Robert’s death and the disintegration of the Frankish camp—demonstrates that Hasting’s forces were agile and opportunistic as well as capable of organized military discipline. His victory here significantly boosted his notoriety in Frankish eyes and likely cemented his position among Viking elites.

Regino’s second major mention of Hasting occurs in 874 during the Breton civil war following the death of King Salomon. Pascweten, one of the contenders for the Breton throne, hires the Northmen—again led by Hasting—to fight against his rival, Wrhwant. While Pascweten ultimately loses, the passage emphasizes how entrenched Hasting had become in regional power struggles. No longer simply raiding, he was now a hired political actor, his forces bolstering the strength of local warlords. The text also describes the Northmen’s retreat into the monastery of Saint Melanius, a detail that mirrors their earlier tactic in 867 and again underscores Hasting’s reliance on fortified sanctuaries when pressed.

Finally, the anecdote involving Wrhwant and Hasting, also from 874, introduces an almost legendary quality to Hasting’s character. Upon hearing that Wrhwant had boasted of standing his ground alone against the Northmen, Hasting invites him to a personal meeting. Wrhwant shows up armed and ready, but Hasting—despite the apparent provocation—does nothing. This story casts Hasting as a calculated commander and a man concerned with image and reputation. He does not engage in a petty clash but reinforces his aura of menace simply by responding to the challenge with composed confidence.

Taken together, these episodes in Regino’s chronicle depict Hasting as a tactically astute, politically involved, and savvy leader.

Annals of Saint-Bertin

The Annals of Saint-Bertin, compiled by court scholars in the West Frankish kingdom, offer one of the most authoritative narrative sources for the Carolingian world in the ninth century. Though Hasting is never mentioned by name, a careful reading—especially when cross-referenced with Regino of Prüm—reveals several entries where his presence can be reasonably inferred. These indirect references are critical for understanding how contemporaries viewed the Viking threat more broadly, and how Hasting likely operated within it.

One such entry appears under the year 869. It describes a peace made between Salomon, king of the Bretons, and the Northmen stationed along the Loire. Notably, the passage also mentions the Viking demand for tribute—silver, grain, wine, and livestock—from local inhabitants, as well as the fortification of towns like Le Mans and Tours to resist further incursions. While the chronicler does not name the leader of the Northmen, Regino’s account of the 867 siege involving Hasting places him in exactly this region, commanding forces active in those cities. Thus, it is not unreasonable to connect the 869 Loire Northmen with Hasting’s contingent, especially given his known role in negotiating truces and extracting tribute from local authorities.

Janet Nelson, in her translation and commentary on the Annals of Saint-Bertin, notes that the narrative of 869 correlates closely with the episode recounted in Regino of Prüm’s 874 entry, suggesting that a lost source or oral tradition may have informed both accounts. In Regino’s version, Salomon later hires the same Loire-based Northmen—led by Hasting—to support his faction in a Breton civil war. The continuity of activity, region, and alliances supports the inference that Hasting was among, if not leading, the “Northmen on the Loire” referenced in the annals.

This indirect style of reference was typical of the Annals of Saint-Bertin, which prioritized a royal, ecclesiastical lens and often collapsed Viking identity into a general category of threat, rather than specifying individual leaders. Nonetheless, when matched with other sources like Regino or the Annals of Saint-Vaast, it is possible to trace consistent Viking pressure across the Loire and Somme valleys, in which Hasting’s role was perhaps central.

While the Annals of Saint-Bertin may not provide a direct testimony of Hasting’s actions, they offer essential context. When read in concert with Regino of Prüm, they help fill in the political and military landscape in which Hasting operated, giving us insight into his role in destabilizing the western Carolingian frontier.

Annals of Saint-Vaast (Annals of Saint-Vaast)

Among the scattered sources that reference Hasting, the Annals of Saint-Vaast offer perhaps the most intriguing clue to his political relevance in the eyes of Carolingian elites. In the entry for 882, a figure named “Alsting,” very likely a scribal or Latinate corruption of “Hasting,” appears. While the annals do not elaborate on his prior exploits, the context in which “Alsting” appears is telling.

The narrative recounts that shortly before his death, King Louis the Stammerer sought out “Alsting” to secure his allegiance. The entry is brief—Louis “intended to gain the friendship of Alsting,” and, we are told, he succeeded. That this interaction is mentioned at all signals the importance Hasting had accrued by the late ninth century. It indicates that Hasting was seen as someone who could be reasoned with, bargained with, and a ruler in his own right, if not in title, then in practical authority.

The brief peace that followed did not last. Later that same year, after the death of Louis and the accession of Carloman, the Annals of Saint-Vaast recount that the Northmen “settled in Condé” and began ravaging the territory with characteristic violence. While it is not explicitly stated that “Alsting” was part of this contingent, the timing and geographical proximity strongly suggest so. If this “Alsting” was indeed Hasting—and if the diplomatic efforts of Louis had momentarily pacified him—the renewed attacks after Louis’ death reflect how closely Viking activity was tied to the shifting tides of Carolingian politics. Hasting may have viewed Louis’ death as a revocation of whatever personal agreement they had shared.

The Annals of Saint-Vaast also contextualize Hasting within a broader shift in Carolingian imperial strategy. The same annal notes that Emperor Charles the Fat granted the Viking king Godfrid the kingdom of Frisia and married him to Gisela, daughter of Lothair. This episode is critical to understanding Hasting’s place in the Carolingian world: kings were now using titles, land, and marriage alliances as tools to pacify and co-opt powerful Viking leaders. Hasting’s rumored elevation to count of Chartres, reported in other sources, fits this pattern. Suppose Godfrid could be made a king, and Rollo soon after be granted Normandy. In that case, Hasting’s transformation from sea raider to regional lord aligns with a broader trend of Viking incorporation.

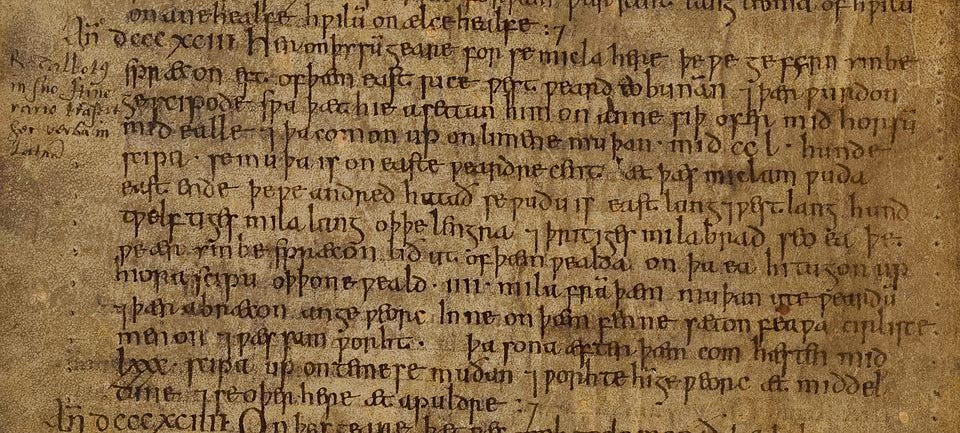

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

By the end of the ninth century, Hasting’s reach had extended beyond the Continent. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle places him firmly in the theater of English resistance. Unlike the terse, dismissive tone common in Frankish sources, the chronicle offers a richer portrait shaped by the politics of its scribes and paints Hasting as a man of sufficient stature to sit across the negotiation table from King Alfred.

The chronicle first names Hasting in 893, describing how he arrived in Kent with eighty ships and constructed a fortress at Milton, while another Viking force landed at Appledore. Rather than combine forces immediately, these two armies held separate ground. The decision allowed Alfred to camp between them and keep their movements in check.

The most revealing moment comes in 894, when Hasting’s stronghold at Benfleet is stormed while he is away. His wife and two sons are captured and brought to Alfred. One of the boys, we are told, was Alfred’s godson—a detail confirming the level of diplomacy that had occurred in prior seasons, when Hasting had delivered hostages and received gifts from the king. Alfred returned the woman and children, in what must have been a deeply symbolic act: a Christian monarch honoring his spiritual obligations to a pagan warlord who had already betrayed him.

But Hasting’s loyalties remained transactional. As soon as he reestablished himself at Shoebury, reinforced by allies from East Anglia and Northumbria, he resumed his raiding campaigns with as much force and cunning as before. His army pressed upriver along the Thames and Severn in one of the most ambitious inland assaults of the period. It was only when a broad coalition of Anglo-Saxon and Welsh forces met him at Buttington that the tide turned. Besieged for weeks and starved of supplies, Hasting’s army ate their own horses before mounting a desperate breakout attempt, which failed.

The trouble with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is that it places Hasting in England in the 890s, which would have made him a very old man indeed. Even if we make him a young man in the 850s and ignore evidence that he was active before then, it means that when he is first mentioned in Frankish sources, he would have been at least in his late sixties, if not pushing eighty. The “age problem” has led several historians, including myself, to conclude that the Hasting of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle may have been a separate man altogether from the one mentioned in Frankish sources. We just don’t know.

What Can We Really Say About Hasting?

In truth, not very much. The historical record is surprisingly thin for a man whose name echoes through medieval chronicles as a scourge of the Carolingian world. Only a handful of sources name him directly—Regino of Prüm, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the Annals of Saint-Vaast—and even these accounts are fragmentary, and focused on specific episodes rather than offering a coherent life story. The rest—such as Raoul Glaber and Dudo of Saint-Quentin—were written a century or more after Hasting’s prime, and are so infused with narrative invention, moralizing rhetoric, and legend-building that they offer more insight into the fears and fantasies of their authors than into Hasting himself.

Even triangulating more reliable sources poses problems. The chronological inconsistencies between accounts raise difficult questions. If Hasting was active in Francia in the 830s and 840s, as most sources suggest, then it becomes difficult—if not impossible—to accept the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s portrayal of him leading campaigns in England in the 890s. If it were the same man, he would have been in his sixties or seventies by then, an improbable age for a Viking warlord in the field. It’s more likely that the chronicle either misattributed the leadership of that campaign or that “Hasting” had become a dynastic or honorific title used by a successor.

Our evidence suggests that Hasting was important—but we’re left guessing at just how important and for how long. The charter recorded in the Cartulaire de l’abbaye de Saint-Père de Chartres (no. 5), dated to 882, confirms that Hasting was granted the county of Chartres by the Carolingian king Carloman II. That charter is often taken as proof that Hasting transitioned from Viking raider to Frankish vassal, and it fits a broader pattern of Carolingian rulers placating Viking leaders with titles and land. But even here, our understanding is murky. The charter survives only in later copies and provides no detail about Hasting’s rule, responsibilities, or ultimate fate.

So while the triangulation of Regino, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the Annals of Saint-Vaast gives us a scaffold for concluding that Hasting was real, influential, and feared, the broader picture remains elusive. He is more than a myth, but far less than a well-documented historical figure. His life emerges in flashes, but beyond those flashes lies a vast darkness.

Ultimately, Hasting remains an enigma. He is a figure defined as much by the ink of fearful monks as by the silence of the archaeological record. It is precisely this ambiguity that makes him the "true and perfect Viking." He embodies the intrepid spirit of the men who betook themselves a-viking. More than that, he serves as a mirror for our own relationship with the past. He represents a Viking Age forever caught between the grandiose mythmaking of the 19th century and the rigorous, often humbling skepticism of modern scholarship. To study Hasting is to accept that we will likely never know the man behind the stories, yet it is within the unknown that our fascination takes root. He stands as a reminder that the Vikings, in all their audacity and complexity, will always remain just beyond our reach—shrouded in legend, distorted by time, and perfectly elusive.

A Note on My Spelling of the Name Hasting

Throughout this article, I use the spelling Hasting, the French version of the name, which reflects my linguistic background and the Frankish sources that most frequently document his activities. The spelling derives from forms such as Hastigus, found in Latinized Frankish chronicles, including ecclesiastical and administrative records. This version aligns with how his name entered the French historical imagination in regions like Poitou, Brittany, and the Loire Valley, where his influence was most deeply felt.

Other historical sources offer various spellings of his name, reflecting regional, linguistic, and scribal differences. A nonexhaustive list includes:

Hæsting/Hæstingus – Found in Anglo-Saxon sources such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, typically Latinized in manuscript copies.

Anstign/Anstignus – A distorted form used by Dudo of Saint-Quentin and later chroniclers, possibly influenced by misunderstanding or deliberate alteration.

Hastenus – Appears in some variants of Frankish annals, a likely scribal variation.

Hæsten/Hasten – A more Germanic form, sometimes found in English or Norse-derived contexts.

Alsting/Alstignus – A corrupted or Latinate rendering from the Annals of Saint-Vaast, possibly a scribal misreading of Hastingus.

Astingus – Found in Raoul Glaber’s Histoires, this Latinized form suggests a vernacular root close to Hasting, perhaps filtered through local dialect.

Given the variance in medieval orthography and the absence of standardized spelling, all of these forms likely refer to the same individual or to leaders within the same lineage or tradition. My choice to use Hasting throughout reflects both continuity with French historiography and a desire for consistency.

Shop my books: