Call of the Open Sea Photos

Photos mentioned in and associated with the book

The following are pictures mentioned in and associated with the memoir titled Call of the Open Sea, an autobiography by Michel Adrien, and translated into English by his grandson C.J. Adrien (me).

From the inside cover: This is one of those stories that sounds so improbable that, were it fiction, we would think it unbelievable. But it's a true story. Michel Adrien’s autobiographical memoir chronicles his extraordinary journey from the war-torn countryside of rural France—where he grew up under German occupation—to becoming one of the 500 wealthiest men in the nation. Leaving behind a life of poverty and wartime scarcity, Adrien embarked on a bold venture into West Africa, where he built a commercial empire that played a pivotal role in the economic development of several post-colonial West African countries.

Remarkable achievements mark Adrien’s life: from becoming a champion tuna fisherman and the first European to employ a mixed African-European crew to facing down Russian economic incursions and rallying allies to save his enterprises to eventually gifting his Senegalese armament to ensure the country’s continued prosperity. His journey is a testament to personal ambition and resilience and a profound exploration of the moral complexities of navigating decolonization and the Cold War.

Translated by his grandson, this memoir offers a rare, firsthand account of historical events from a unique perspective, providing valuable insights into the intersections of race, power, and legacy. Michel Adrien’s story is a powerful reminder that truth can be stranger than fiction and that our choices leave legacies long after we are gone.

Michel Adrien at thirteen years old, sitting on his father’s boat, the Fleur de Mai.

Michel Adrien with his mother Marie-Joseph, circa 1939. Michel was an only child for the first ten years, during which he benefited from all his mother’s love.

Michel’s broken clog, which his father repaired with a spare piece of leather. His father, Emile Adrien, had borrowed the clogs from his boss.

Micheal with his mother.

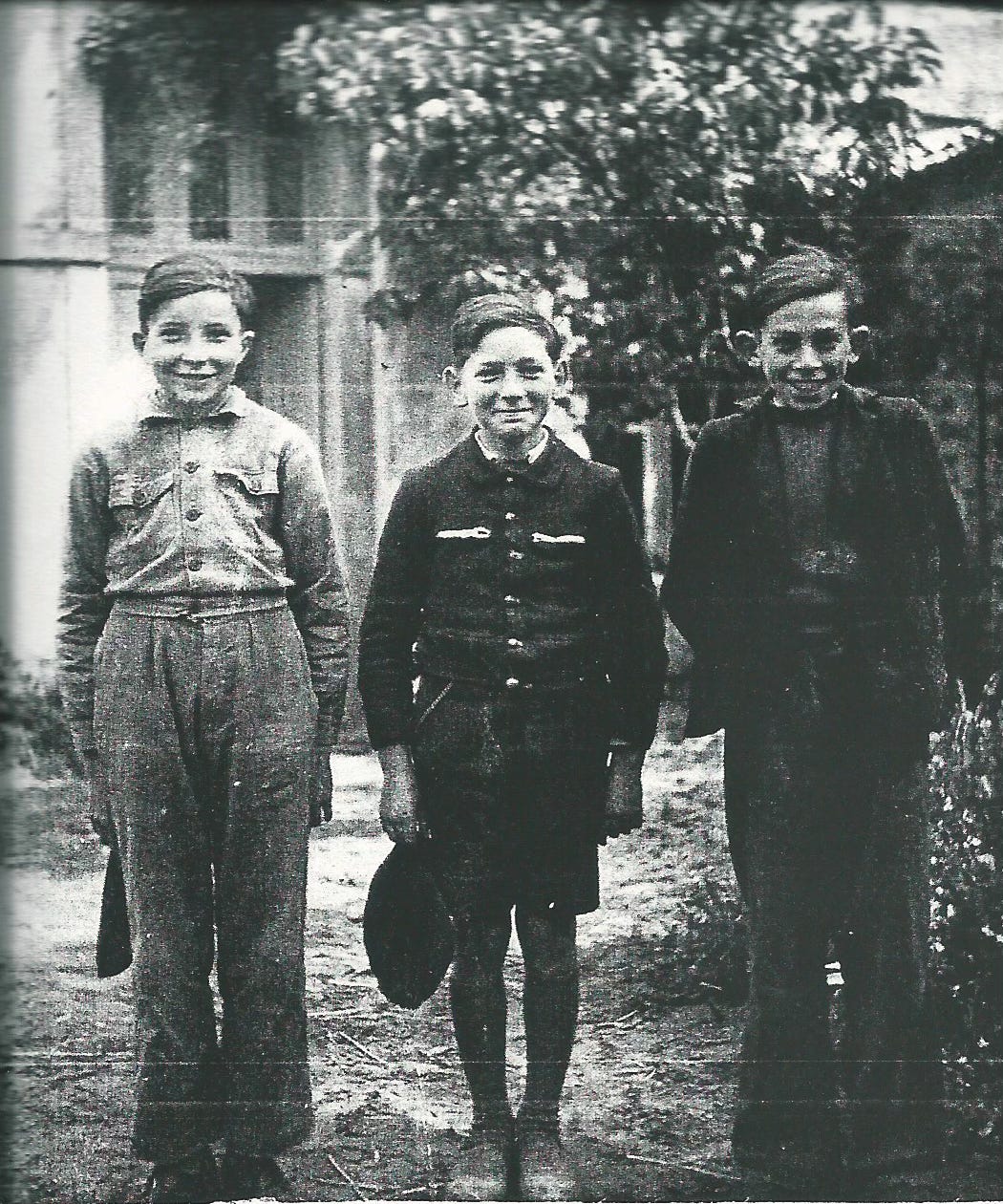

Michel with his friends Gilbert Fradet (left) and Noël Monnier (right) on the day they received their certificate of completion for primary school. All three would be plucked from school to work on fishing vessels as cabin boys. Gilbert and Noël later drowned in their first couple of seasons.

The carcass of the Fleur de Mai after the shipwreck. Without Michel’s ability to swim—he was the only one onboard who could—none of the crew would have survived.

Another view of the Fleur de Mai after the shipwreck.

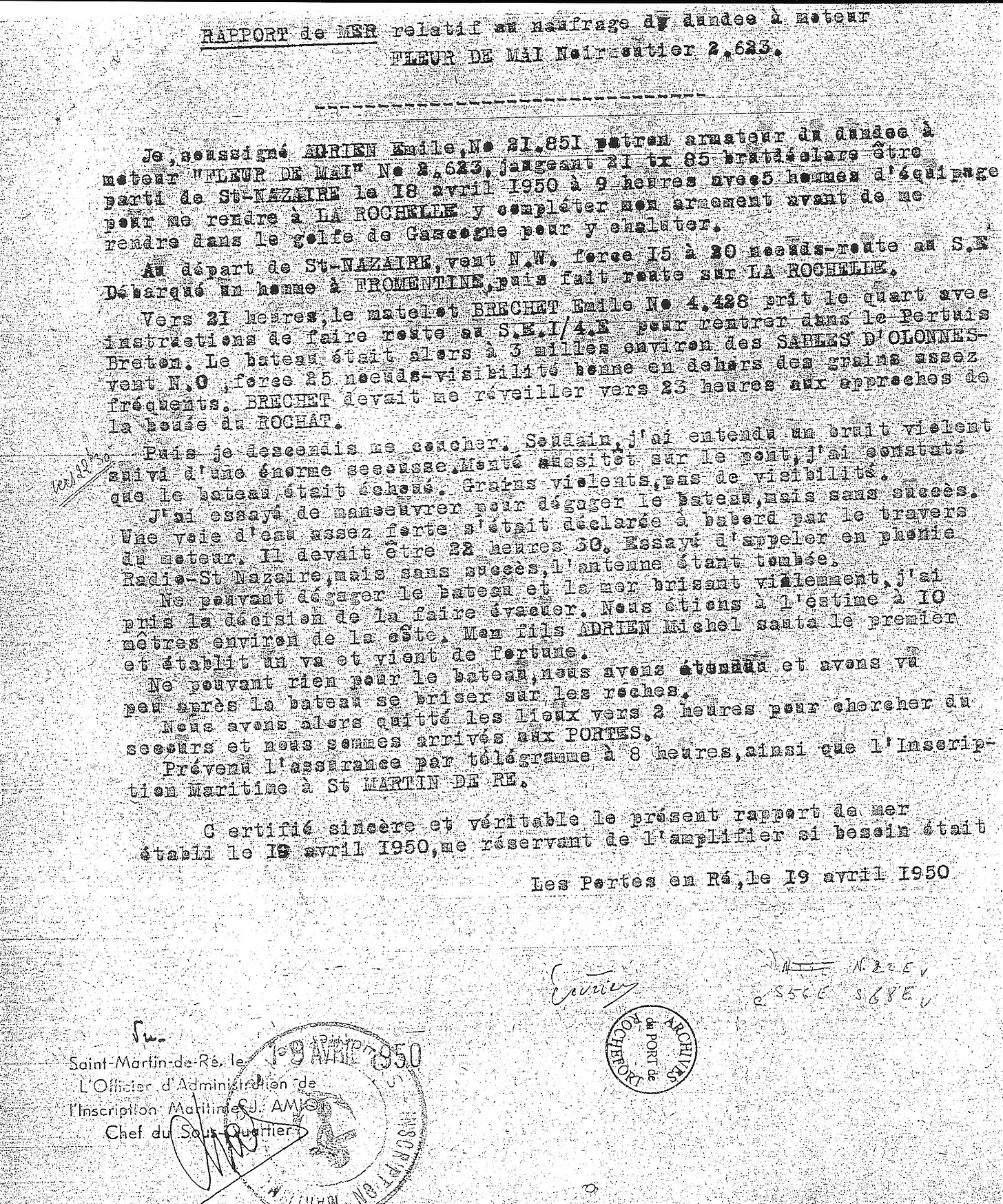

The official report by the maritime authorities of the shipwreck.

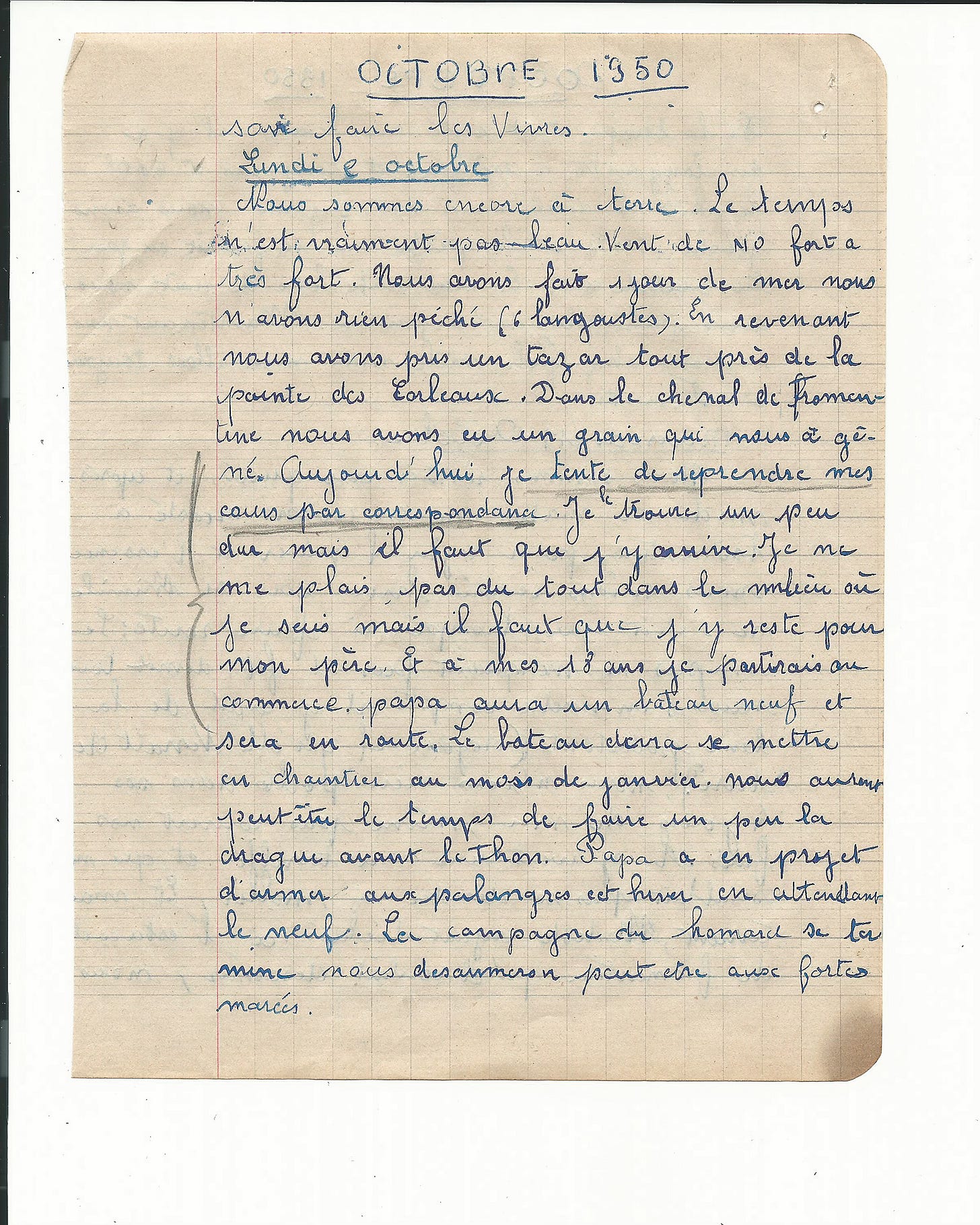

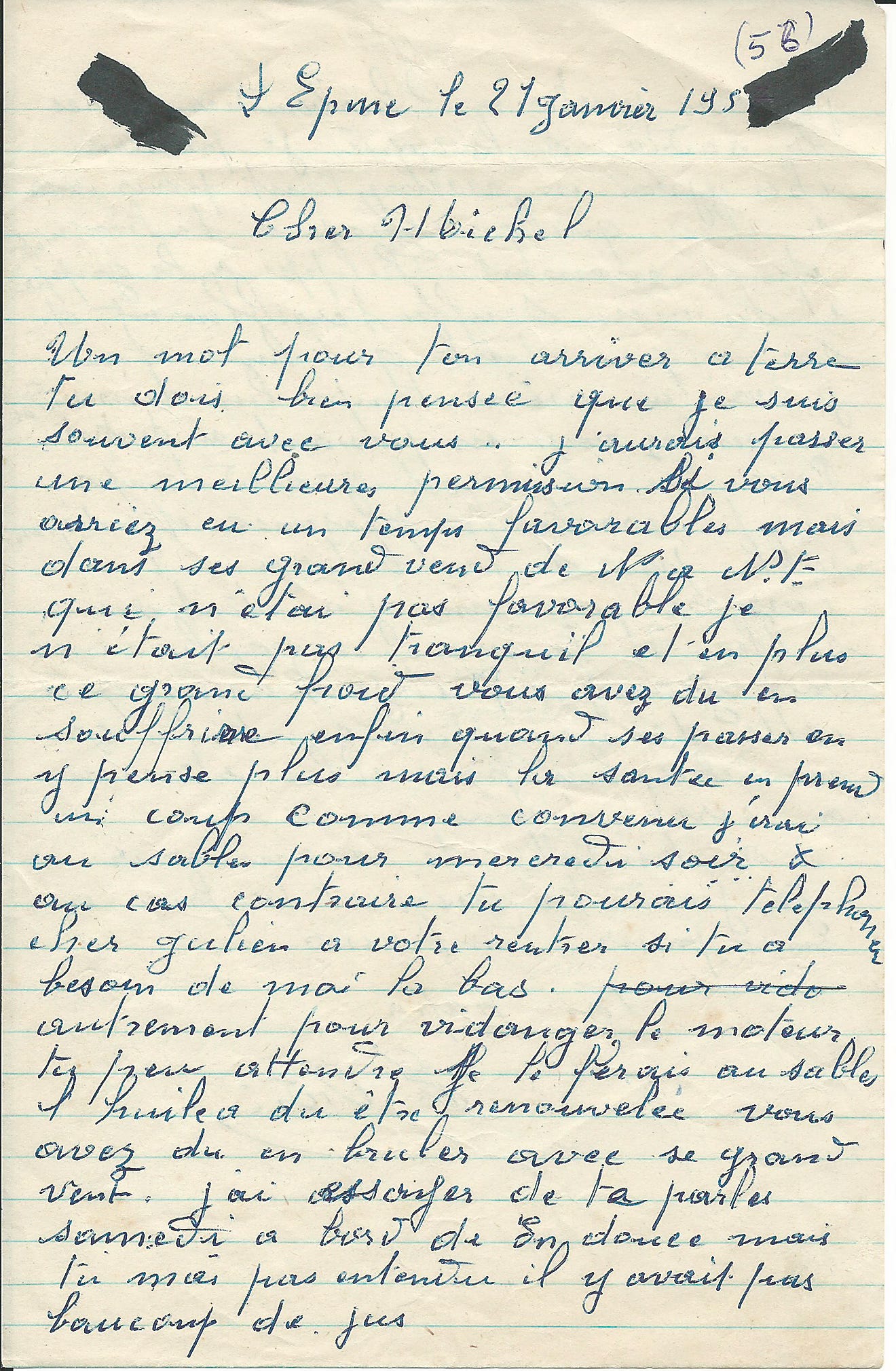

A page from Michel’s personal journal speaking to the hard conditions at sea.

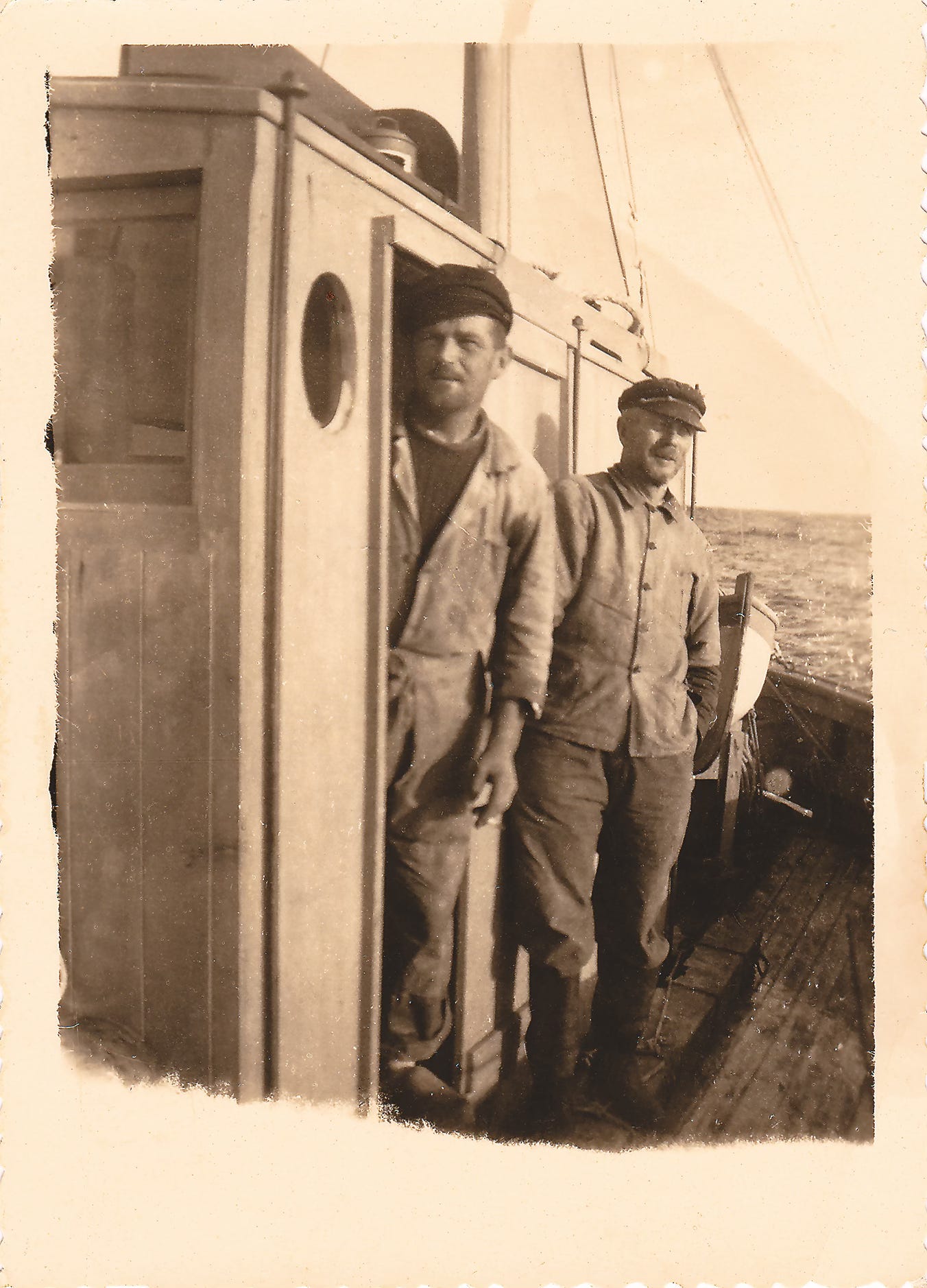

Michel’s father Emile (left) and his uncle Jacques (right) aboard the Fleur de Mai.

A page from Michel’s personal journal in which he recounts the painful death of his uncle Jacques, who died of a perforated stomach at sea.

Michel, in 1950, aboard the Fleur de Mai, sailed alongside a tuna boat still propelled entirely by sail.

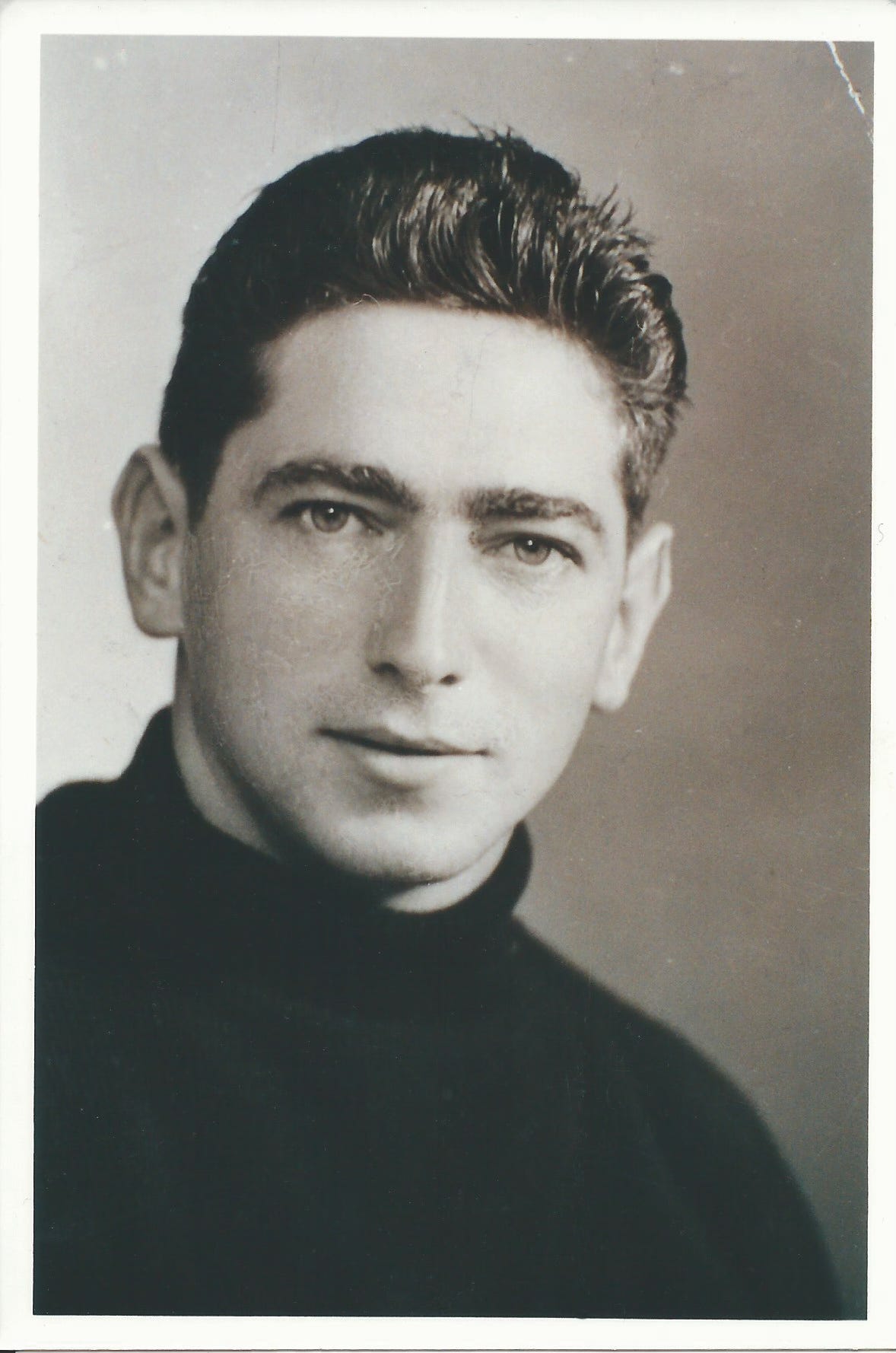

Michel in 1955. He was 22 years old.

Michel’s future wife Jeanine on the day they met on September 11, 1955.

A letter from Emile Adrien to Michel, giving him command of the Fleur de Mai while he was recovering from illness.

Jeanine on her first visit to Michel’s home village of L’Epine. She caused quite a stir in the local religious community as her attire was considered scandalous.

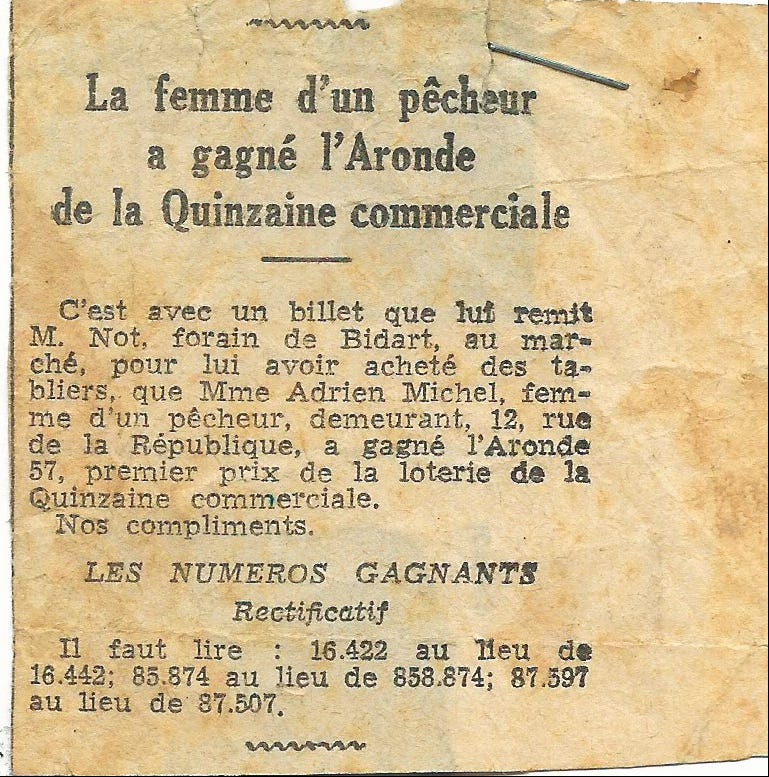

A newspaper clipping showing Jeanine had, in fact, won a car in a local raffle.

Michel and Jeanine standing beside the car Jeanine won in the local raffle. It was their first car!

Michel posing in front of the stern of the Fils de la Vierge during its construction.

Newspaper clipping of the completion and launch of the Fils de la Vierge.

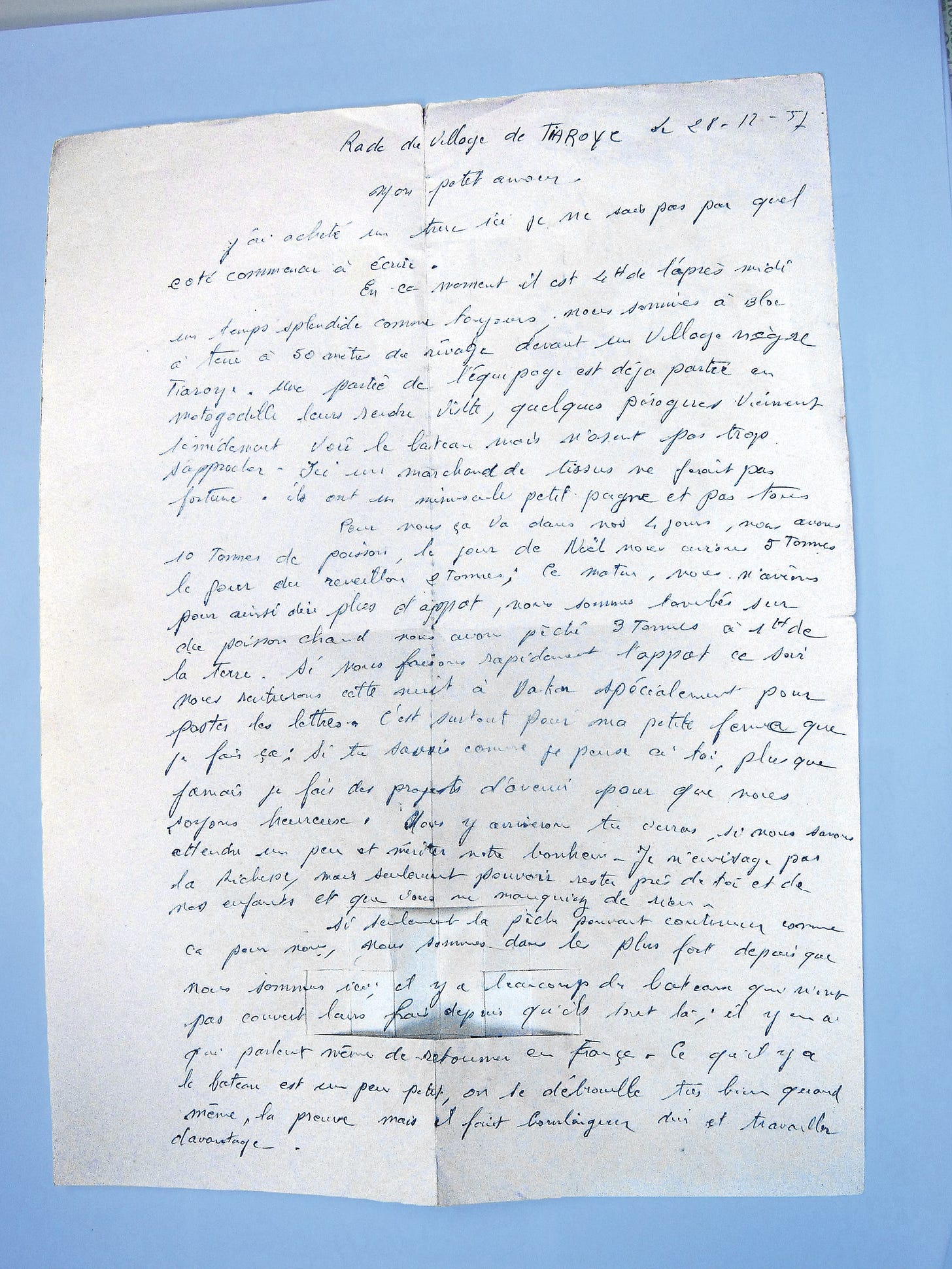

The first letter Michel wrote to his wife from Africa.

Michel sailing by sextant off the coast of Guinea.

Michel with his crew. It was the first-ever mixed crew of Europeans and Africans, and Michel was told he would not succeed with such a crew. They won the annual tuna fishing derby three years in a row together. The Europeans pictured are, starting in the first row, Germain de St. Gilles, Jean Krabzca, Charles Rivarin, Joseph Monnier, and André Berthomé. To Michel’s left is his bosco, Thiaré Ansou, who recruited and managed the African sailors. The African sailors were all from the Saloum region of Senegal.

Michel’s crew is repairing nets at the port of Dakar.

Le Fils de la Vierge after being outfitted for coastal fishing. Note the crew is almost entirely African. Michel thought they were better workers than the Europeans!

Michel tuna fishing with his live bait technique.

Another photograph of tuna fishing.

Fils de la Vierge in October of 1958 at the port of Noirmoutier, a few days before departing for Africa.

Fils de la Vierge as it departed for Africa.

A newspaper clipping about the Fils de la Vierge’s departure.

Another newspaper clipping of Fils de la Vierge’s departure.

A newspaper clipping from the spring of 1960 from the Senegalese newspaper Quotidien National reporting that the Fils de la Vierge had held the tuna fishing record from 1957-1960 in a derby that comprised French, German, Russian, and American ships and that it had done so with the only ‘mixed’ crew of Africans and Europeans.

Fils de la Vierge holding 32 tonnes of tropical fish. This was the first major catch after refitting the ship with new nets to fish in shallower waters.

Senegalese fishermen repairing the nets.

Michel and Jeanine’s house in Dakar.

Mamadou Sané and his wife Maïmouna, who cared for the Adrien home in Dakar until their departure in 1998.

Jeanine and the children in the village of Pout, on the outskirts of Dakar.

The masthead of the Fleur de Mai, which Michel has kept to today.

The inaugural voyage of the Cap Rouge to Senegal in 1968. It was the fourth ship in Michel’s fleet, and the first in a new generation of trawlers that would see his commercial enterprise rise to new heights.

Michel’s permit to export products through Liberia, which he obtained through a long series of rather unbelievable events.

A remittance notice from Starkist Tuna, an American company, whose founder and C.E.O. John Radine helped Michel navigate an economic incursion by the Russians in West Africa.

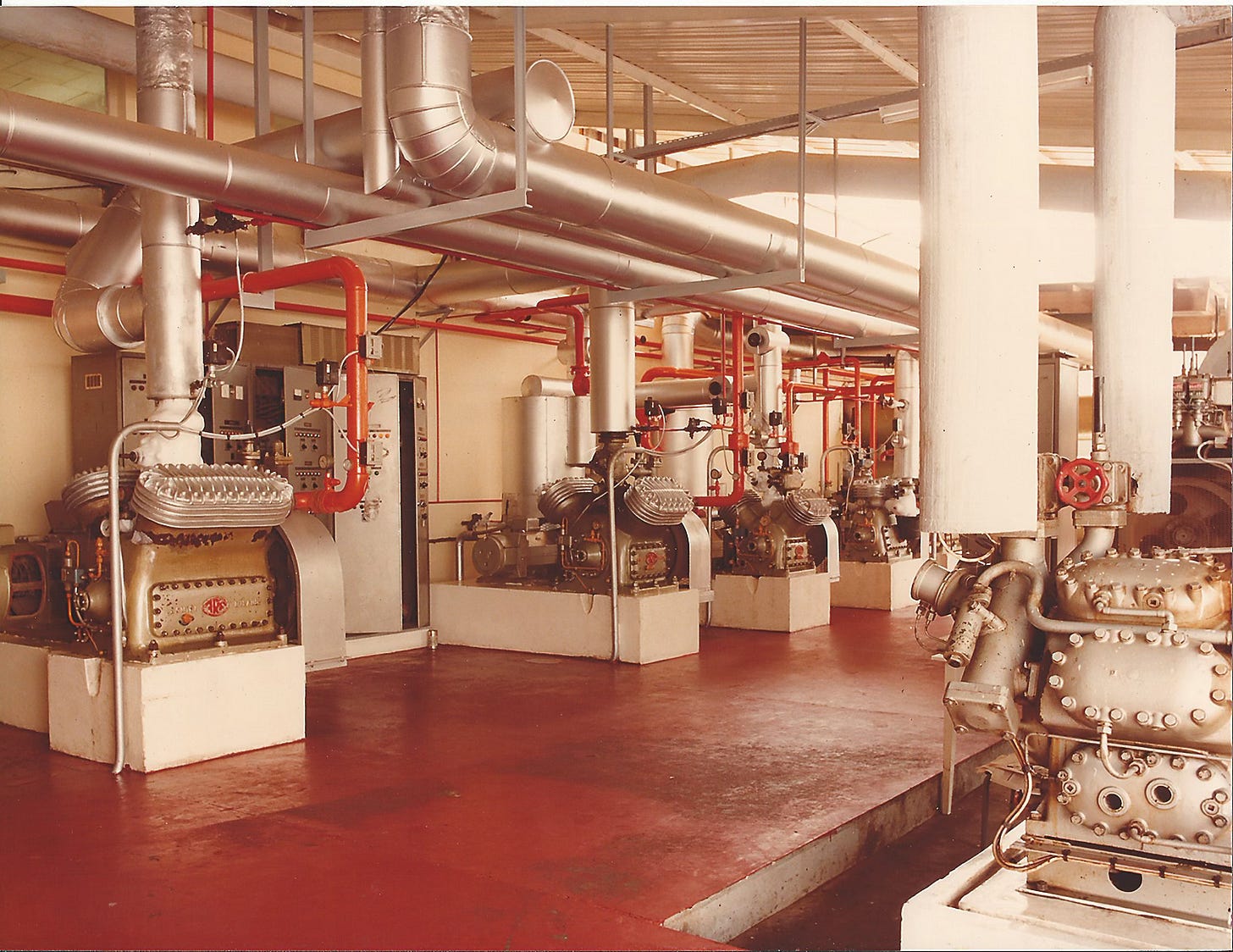

The newly built processing plant Adripeche, opened in 1971.

The mechanical room for the factory, showing just how much refrigeration power was needed to keep Adripeche’s production frozen.

A clipping from the economic journal AFRICA explaining the size and scope of Michel’s enterprise by 1973, showing over 1,000 employees and over one billion Franks CFA (West African Franks) in annual revenue, equivalent to about $17 million at the time. In today’s money, that’s about $85 million per year.

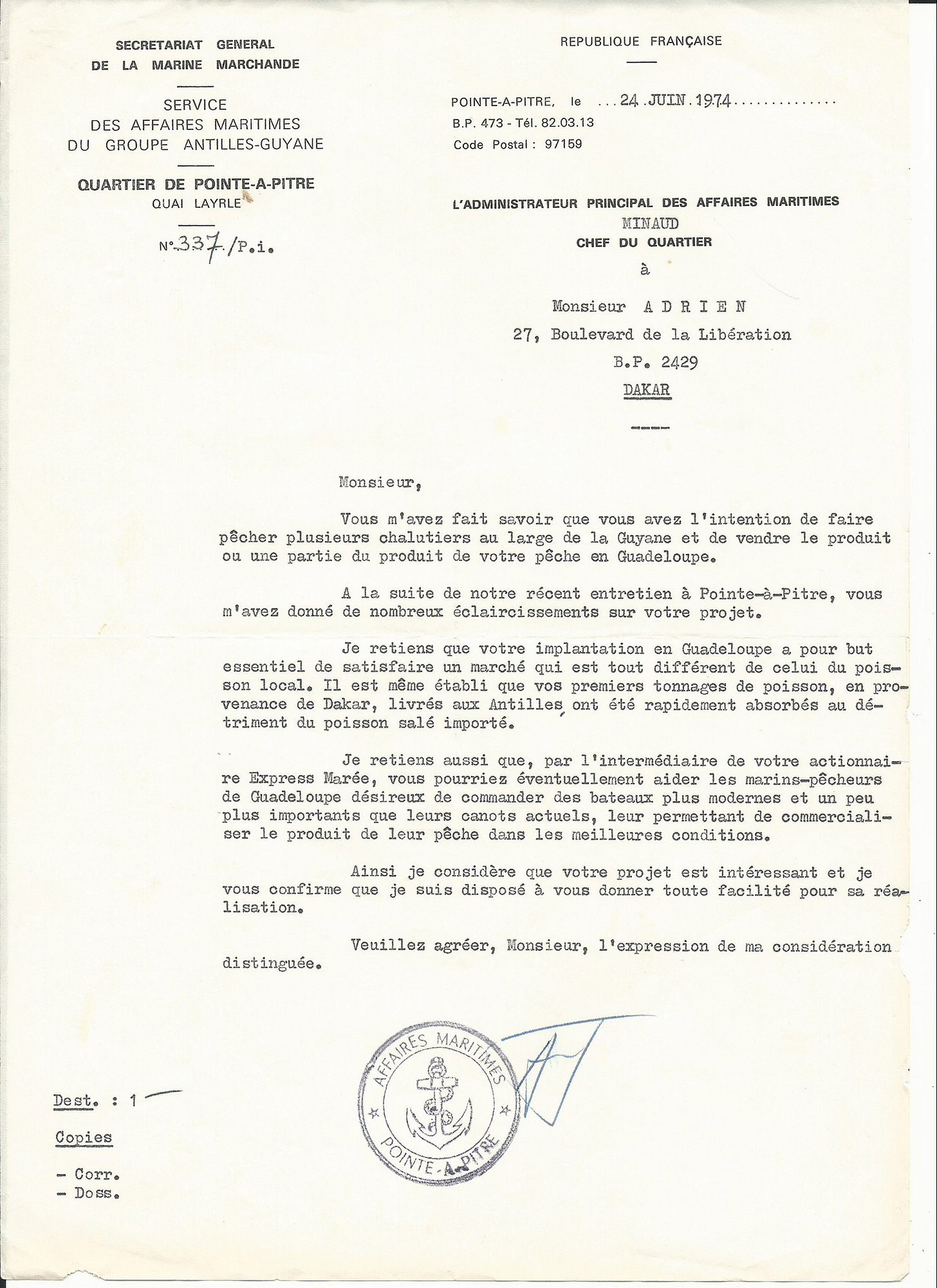

A letter from the Office of Maritime Affairs confirming that the frozen cargo of tropical fish from Senegal successfully reached the Antilles and sold in its entirety. It was the beginning of a new adventure for Michel on a new continent.

Niam Niokho, where Michel and his family retreated to relax away from the hustle and bustle of his new business empire.

Michel is with his son René and his daughter-in-law’s parents at Niam Niokho.