How a Monastery Became a Fortress in the Face of Viking Raids.

A Deep Dive into the Viking Invasions of Western France — Episode 4

Last week, we looked at Pépin I’s toll exemption of 826, a revealing glimpse into how royal policy adapted to the growing pressure of Viking activity along the Loire. The exemption made clear that by the mid-820s, Scandinavian raids were disruptive enough to justify granting Saint-Philibert’s monks financial relief. This was in addition to the charter from 819, which had given the order of St. Phiblert the right to construct and flee to a satellite priory, called Déas, further inland each year during raiding season.

This week, we move forward just a few years to 830, when the situation had escalated from fiscal concessions to an attempt at physical fortification. A royal diploma dated 2 August 830 says the monks of Saint Philibert had fortified their island house on Herio and received imperial permission to post men to guard the castrum. The same act reports that, despite the fort, the community still left the island each summer for Déas. It even notes the headaches of that move: transporting church goods was hard, and divine service on the island stopped while they were away. A fort, a garrison, and a scheduled seasonal withdrawal point to an ordinary risk that returned year after year, not a single emergency.

The document sits in a line of evidence that already casts the threat as recurring. In 819, Abbot Arnulf obtained approval to use Déas as a refuge in the face of frequent incursions. The tone in the sources does not relax in the 820s. The prologue to Ermentarius’ Miracles—Ermentarius of Noirmoutier was a ninth-century monk and alleged eyewitness to some Viking attacks, and he left us one of the earliest narrative sources in his Miracles of Saint Philibert—complains about constant disruptions by the Normans, especially for the families attached to the monastery’s service, and mentions inhabitants of the islands fleeing with their lord. Later, Book II places Count Renaud of Herbauge fighting the Vikings while defending the castrum. Whether that clash occurred exactly in 835 or another nearby year, it confirms that the fort was built to address a problem that would not go away.

This matters for how we tell the story of the Loire before the big annals pick up the narrative. The 830 diploma implies that fortification had already taken place and that the summer evacuation was already a habit. In other words, the ‘frequency and intensity’ of Scandinavian raids noted in 819 did not fade during the decade that followed. They persisted through the 820s and by 830 had produced a standing policy on Herio: build, guard, and when the season turns, leave.

If earlier parts of this series asked whether 799 began something and whether the rhythm continued, this entry provides the administrative proof. A charter that authorizes guards is a government response to a known and repeated threat. Read alongside Ermentarius’ testimony and the notice of fighting at the fort, the picture is clear. Regular Scandinavian raiding along the lower Loire is already visible before the better-known entries in the major annals.

Today, when visiting the castle of Noirmoutier, visitors can learn about its history, including how it was built to repel the Vikings and stands as the oldest castle in France. While the evidence is lacking to show that the castle that stands there today is in any way derived from the castrum intended to fend off the Vikings, one thing remains certain: not three decades into the three centuries that would become known as ‘The Viking Age’ the so-called Vikings were already having an impact.

This idea of the castrum is a central component of my novels. In the second tome, In the Shadow of the Beast, my main character Hasting takes the castrum and monastery over to use as his base of operations in the area.

If you can’t wait until next week to hear about the next phase of Viking expansion in the Carolingian realm, live it in my series, The Saga of Hasting the Avenger, which culminated in the epic battle on the island of Noirmoutier between a Frankish army and the most notorious Viking warlord of them all, Hasting.

Sources (via Cartron, p. 34, n. 12): Diploma of 2 Aug. 830 (ed. L. Maître, “Cunauld, son prieuré, ses archives,” 250–253), with confirmations in the Annales Engolismenses (MGH SS XVI, a. 834, 485) and the Chronicon Aquitanicum(MGH SS XVI, a. 830, 252); Ermentarius, Miracula I, Prologue; Miracula II, c. XI.

Author Update

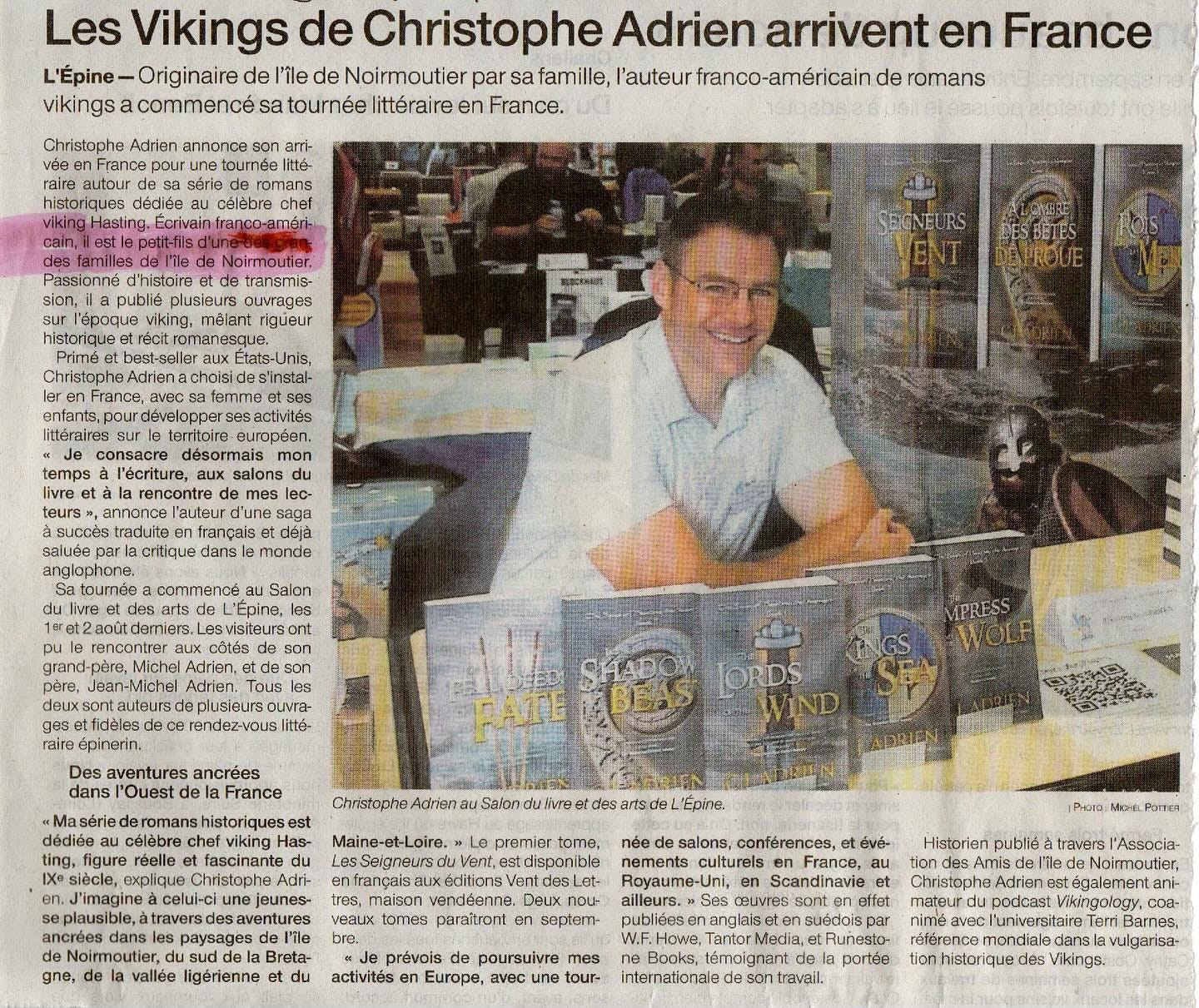

For those of you curious to follow my new adventures on the book circuit in France, I have a few updates to share with you. First, I am ecstatic that I was the one author at my last show chosen to be featured in Ouest France:

I was also on the local radio with NovFM earlier this month. If you’d like to hear me speaking in French, you can access the clip here: Les Vikings S’Invitent A Noirmoutier. NovFM has invited me back for a longer form interview later this month.

I was also invited for an interview on RCF Radio. We recorded this past week, and the show will air in September:

September is shaping up to be an exceptionally busy month. I have a show in Dompierre-sur-Yon on the first weekend, a show at the Châteaux de Roiffé the next, Le Salon de Noirmoutier on the third weekend of the month, and finally a book fair at the Château de la Flocellière on the last weekend in September. You read that right—two of my shows are going to be in CASTLES. How cool is that??

Bref, things are going well. Thank you to everyone who is following my journey and has read my books, and if you support what I’m doing and want to help out, consider purchasing a premium subscription on Substack. Every one goes a long way to help keep this dream of mine alive! Thank you 🙏