These Were the Walls the Vikings Touched (and Burned).

Explore L'Abbatiale de Déas in St. Philbert de Grand Lieu, one of the oldest medieval structures still standing in Europe.

First, a personal note:

This article is the first in my new planned content style for my Substack, because, frankly, I have decided to stop talking exclusively about Vikings all the time. I still love them; they have paid my bills and given me many books’ worth of material, but now that I am living in France again and wandering into all these incredible historical sites, it feels a bit ridiculous to pretend the rest of the Middle Ages, and indeed the rest of history, does not exist. So I am opening things up. Expect more travel chenanigans, more diverse sites, more strange little pockets of medieval history, and plenty of Viking mischief whenever it fits. This shift also brings my Substack more in line with the videos and travel content I have been making on social media, which feels much more like the direction my work is naturally heading. For this first article, I thought I would ease everyone into the new format with something Viking-adjacent.

Thank you all for subscribing!

Explore L’Abbatiale de Déas in St. Philbert de Grand Lieu, one of the oldest medieval structures still standing in Europe.

The Viking Age was a long time ago. Not many buildings from that era have survived intact over the centuries. Fire, war, renovation, collapse, and the simple passage of time have erased most physical traces of the world the Vikings knew. But L’Abbatiale de Déas in St. Philbert de Grand Lieu stands in that rare category of “somehow made it,” and is one of the oldest medieval structures still standing in Europe.

My wife and I visited recently, arriving between noon and two, which, as any seasoned traveler in France will tell you, is a cardinal sin. Everything is closed in small towns. Everything. So we did what one does when one has committed this unforgivable error: we surrendered to fate and begrudgingly took refuge at the local crêperie. I say “begrudgingly,” but the truth is we were rewarded with some of the best galettes we’ve had since moving back. France punishes you and rewards you in equal measure.

We were in the off-season, so when we finally made it to the abbey, we had the whole place to ourselves. The young twenty-something woman at the front desk probably regretted saying “Let me know if you have any questions,” because I immediately cornered her with more information about the Vikings than she ever wanted to know. She was polite, smiled through it, and will probably tell her friends that a very enthusiastic (or, as my wife insisted, good-looking) American man with impeccable French showed up and talked her ear off.

The grounds outside are lovely. Broad lawns, stone walls, and the quiet flow of the river close by make for an inviting afternoon. I made a video for Instagram and TikTok, because of course I did; that’s half the reason I go anywhere now. While filming, I accidentally startled a poor woman who was trying to nap in the grass. Moments later, we were startled in turn by a very drunk, very chatty man on a bike. The medieval world is gone, but human nature has changed remarkably little.

And then we went inside.

The interior of St. Philbert hits you like walking into the halls of Moria: massive pillars lift a great vaulted ceiling that seems to swallow sound. It’s surprisingly clean in there, almost unnervingly so. My wife, who is into what I affectionately call “ghost shit,” was scanning the place for any kind of lingering presence. After a minute, she frowned and said, “Nothing. Totally blank.”

“Yeah,” I told her, “that’s because the Vikings attacked this place a decade after it was settled, everyone fled, and it basically sat empty until some rich guy turned it into a museum in the 1890s.”

Indeed, St. Philbert’s story begins in 819, when the abbot Arnulf secured permission from Louis the Pious to build a safer monastery for the community of St. Philibert. Their original home was the island of Noirmoutier, which by that point had been hit with “frequent and persistent” Viking raids. I cover the earliest phase of the incursions in my series on Brittany’s first encounters with the Northmen.

By 836, the monks relocated permanently to L’Abbatiale de Déas, hauling their relics and their entire monastic world inland. They hoped distance would protect them. It didn’t. In 847, the Vikings “found” them again, but this time the monks received a warning and fled before anyone was harmed (though I am certain the Vikings still burned through the roof down). Thus began the next chapter of their long wanderings, eventually settling at Tournus much farther east, leaving L’Abbatiale de Déas abandoned to time, weather, and whatever wandering souls happened to pass by.

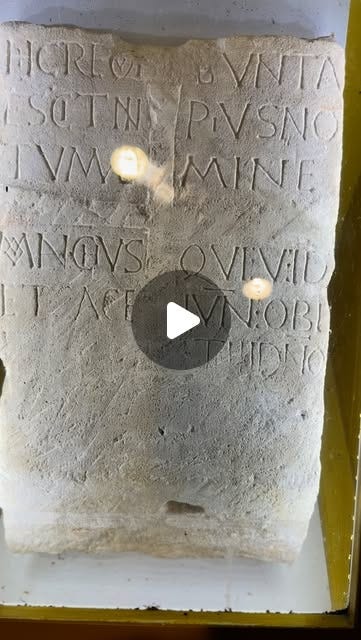

It wasn’t until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the abbey rose from obscurity. It was declared a national heritage site, restored, given a proper roof, and reopened to the public. Now you can stand inside those quiet, echoing halls, run your hands along those ancient pillars, and touch the same stones the Vikings touched.

Oh, and here’s the video I made for Instagram/TikTok:

And a very much less serious version: