Viking Armor: What did the Vikings Wear Into Battle?

If modern movies and TV shows were any guides, they would have us believe the Vikings were some kind of leather-clad biker gang. This begs the question: what did the Vikings really wear?

If modern movies and TV shows were any guides, they would have us believe the Vikings were some kind of leather-clad biker gang. Costume designers, thankfully, are not authoritative on the subject of medieval arms and armor. Their goal is flair, and to draw the eye. This begs the question: what did the Vikings really wear?

The Three Phases of Viking Expansion

When considering the real Vikings, i.e. those who roved across Europe over 1,000 years ago, it is first important to understand that the Viking Age lasted over three centuries, during which styles and clothing changed. Early raids in the 8th century were carried out by small war-bands, or drott, whose purpose was to pillage and acquire wealth. One hundred years later, the war-bands evolved into bonafide armies to suit the ambitions of increasingly powerful warlords. Repurposing their warriors for invasion required a refitting of their arms and armor to adapt to the conditions of larger confrontations.

It is clear from the evidence that once the Viking Age had started, raiding efforts ratcheted up with each passing year. The historian Lucien Musset, known for his work on the Norse incursions in France, identified three distinct phases in the Scandinavians’ westerly expansion into Christian Europe. In the first phase, ships appeared spontaneously and sought purely to raid; they progressively worked their way from coastlines to rivers, and eventually pillaged hundreds of kilometers inland, away from the sea. The second phase began when the Vikings struck at the heart of organized states. They leveraged their violent reputation not to raid but to persuade local populations and their governments to pay them off to keep the peace. The payments received the name Danegeld, or money paid to the Danes. Lastly, the third and most devastating phase involved the establishment of direct control over ravaged regions whose governments had grown too defunct to pay a Danegeld. The Vikings installed indigenous puppet autocrats who helped to legitimize their seizure of land and the wealth it produced.

Looking more closely at specific regions, Musset’s three phases took varying forms depending on the societies the Vikings encountered. In Ireland, Scandinavians attempted invasions and colonization attempts almost immediately after the first raids. England, in contrast, was raided for several decades before more organized armies landed ashore. Further south, in France, Norse raiders struggled to mirror their successes in the British Isles until fractures within the Carolingian empire opened the door for them to launch bolder incursions upriver. The region of Bretagne, in particular, experienced the full breadth of each phase perhaps more than any other region in Western Europe outside of England. Sporadic raids plagued its coastlines for three decades before transitioning to four decades more of paying Danegeld. By the end of the 9th century, the Vikings had established direct control over nearly the entire region and they had occupied its largest city, Nantes, which they had seized from the Carolingians and called Nambørg.

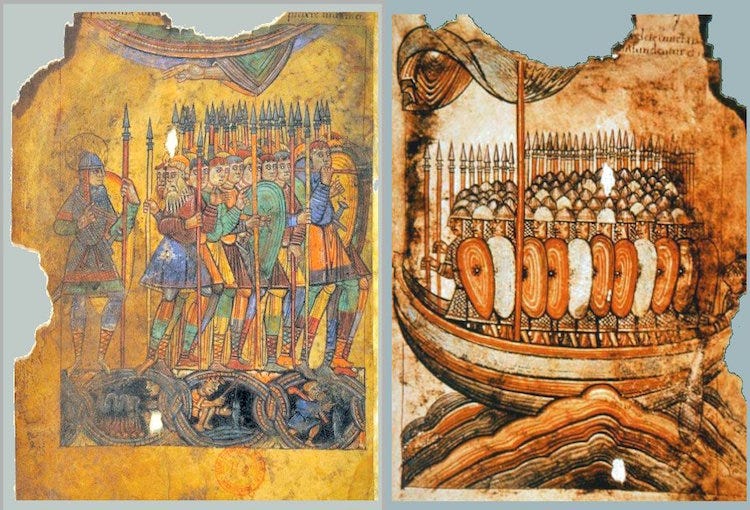

A Viking fleet approaches Guérende with the aim to invade, from the Vita of St. Aubin. Note that all the "Vikings" (on the right) are wearing maille and helmets.

Each phase of expansion required a different set of tools. Sporadic raids needed to be quick, and so heavy armor would have made little sense to wear. By the second phase, a war-band’s leader, or drottin, might have accumulated enough wealth to buy his men better arms and armor, in case the locals decided to fight back during a demand for Danegeld. Once they had made the transition to the third phase, the Vikings took on the look of a more organized army, funded by a stronger, wealthier, and more established monarch.

They wore what they could afford

A passage from the Heimskringla relates to us the attire of Olaf Haraldsson’s warriors on the eve of the battle of Nesjar, which took place in the early 11th century: “King Olaf had in his ship 100 men armed in coats of ring-mail, and in foreign helmets.”

Arbo's "Olav den Helliges død" a representation of St. Olaf's last battle, ostensibly wearing foreign ring-mail and helmet.

The passage is telling insofar as it demonstrates Olaf’s largesse, or generosity of wealth. To afford maille and helmets for 100 men would have cost a fortune. It also tells us foreign arms and armor had the reputation of better quality, else Olaf would have purchased Norse equipment. We know from the earliest sources on the Viking Age that a massive black market for Carolingian arms and armor existed in Scandinavia, and the rulers of the Carolingian empire made numerous attempts to stem the flow of equipment north. Nothing irked Charlemagne more than having to fight a battle against his own weapons and armor.

For most of the Viking Age, it seems, foreign arms and armor were the coveted jewels of the Vikings. Carolingian equipment seems to have been particularly in fashion. The brunia and Carolingian sword were explicitly banned from trade in the capitulary of Boulogne, which states:

“It has been decreed that no bishop or abbot or abbess or any rector or custodian of a church is to presume to give or to sell a brunia or a sword to any outsider without our permission; he may bestow these only on his own vassals. And should it happen that there are more bruniae in a particular church or holy place than are needed for the people of the said church's rector, then let the said rector of the church inquire of the prince what ought to be done with them.”

Charlemagne made numerous attempts to stem the flow of arms and armor into Scandinavia for fear his soldiers might have to face equally well-equipped enemies. That such explicit attempts to prevent brunia and swords from falling into Viking hands tells us the demand for such goods in Scandinavia may have been quite high.

If imported arms and armor were the norm, then wealth played a crucial role in what a Viking would have worn. Olaf may have bought expensive arms and armor for his closest lendirrmen, but the rest of his army would have been expected to furnish their own. Particularly in the early Viking Age, most Vikings likely left home with little more than a hand-made shield and a spear or wood-cutting ax, and he would have worn thick wool clothing. Thick wool can soften the blow of a weapon, protect against slashing (to a certain extent), and it served the double purpose of keeping the wearer warm at sea. Wool insulates even when wet. Perhaps the leader of the war-band wore a helmet or brunia (a maille shirt made in the Carolingian Empire) he bought at a market, but he would have been the only one so well-equipped.

European Maille Hauberk (brunia)

Later in the Viking Age, as warlords increased their wealth, worthy warriors would have received gifts in the form of expensive arms and armor, in addition to their share of the spoils of raids and conquest. With the men who proved themselves the most to their leader improving the quality of their armor, we might expect there to have been a sort of meritocracy of arms and armor, where the most lethal, most loyal men wore the best equipment.

They adapted to the lands they roved

Arms and armor are generally adapted to the conditions of warfare in a given region. Since the Vikings roved all across Europe, it is no surprise their arms and armor differed in style and utility based on where they preferred to conduct business. The ship burial on the island of Groix, off the coast of France, gives us some indication of the lengths to which the Vikings went to adapt their equipment to the fighting styles of their enemy.

The Bretagne region of France had remained culturally and ethnically Celtic since the withdrawal of the Romans and fought with a semi-Roman style they had inherited from their Roman-Briton ancestors. They used javelins with soft tips that, when penetrating an enemy shield, bent with the weight of the shaft to render the defender’s shield useless. The ship burial at Groix revealed an array of shield bosses unlike any other in the Viking world. Side by side with shield bosses more typical of the ones found in Scandinavia, archeologists found unique designs, which they believe were attempts to adapt their arms and armor to the fighting conditions in Brittany.

Shield Boss designs from the Groix Ship Burial

Far in the East, we see a similar pattern in the evidence. As more warriors from Sweden, called the Rus, joined the Varangian Guard, an elite corps of soldiers who answered directly to the Byzantine Emperor, their arms and armor adapted to the fighting conditions of the Middle East. An illumination from the Skylitzis Chronicle shows the Varangian Guardsmen as wearing what appears to be Lamellar armor, a type of interlaced scale armor not woven to the undergarment. Nine pieces of lamellar, or scales, were found in a grave in Sweden, likely an import from someone who either purchased or received the armor as a gift in Constantinople. That so few lamellar pieces have ever been found in Scandinavia is also telling—it seems the Rus did not see value in bringing that style of armor home, perhaps preferring the brunia when fighting their kin.

Varangian Guardsmen, an illumination from the Skylitzis Chronicle

What did arms and armor did the Vikings wear?

When approaching the question of what arms and armor the Vikings wore, we must look at four main factors: who, in particular, are we talking about; where did they rove; what was their business in the places they roved (i.e. what phase of expansion are we talking about); and when are we talking about. Only when we consider all four of these factors can we say anything about what a Viking or group of Vikings may have worn. All we can say more broadly is that the evidence tells us the Vikings wore what they needed to wear, or what they or their patron chieftain could afford.