Was the Hundred Years' War a French Civil War?

How the Succession Crisis that Contributed to the Opening of Hostilities Could be Viewed by a Different Lens.

Over the past few weeks, I have been neck-deep in brushing up on my Hundred Years’ War history in preparation for the course I’ll soon be teaching for Medievalists.net. It’s been so much fun opening up the proverbial can of worms and diving in, looking at causes, triggers, and events from as many angles as my subjective little brain can handle. One angle, in particular, I felt was worth sharing, not least because it led to a good laugh. It has to do with the succession crisis of 1328 that allegedly was the ‘cause’ of the Hundred Years’ War (though that notion has been challenged). Looking at the evidence, I believe we might call the first phase of the Hundred Years’ War a “French Civil War.”

To understand my thinking on this, we need to go back 150 years to the succession crisis in England called the Anarchy.

When Henry I’s son, and only heir, died at sea, he asked his nobles to support his daughter, Matilda, to succeed him. But Henry had made the mistake of marrying her off to Geoffroy Plantagenet, Count of Anjou (in France), as a means to buffer the French king’s power vis-à-vis the duchy of Normandy. Geoffroy was unpopular among the Anglo-Norman nobility because he was their traditional enemy. When Henry kicked the proverbial bucket on December 1st of 1125, his nephew Stephen of Blois, who was count of Boulogne (in France) by jure uxoris (through his wife), gathered support and took the throne to “preserve stability in the realm.”

Matilda took action. She moved to Normandy and sent letters to gather supporters in England. Many rallied to her cause. By the time she landed on English soil in 1139, she had enough support to fight a successful campaign. In 1141, her forces captured Stephen, and she planned to crown herself queen. Unfortunately, she remained deeply unpopular in London and had to flee after an uprising. Stephen’s wife led an army that captured Matilda’s uncle, and she was forced to release Stephen in the exchange.

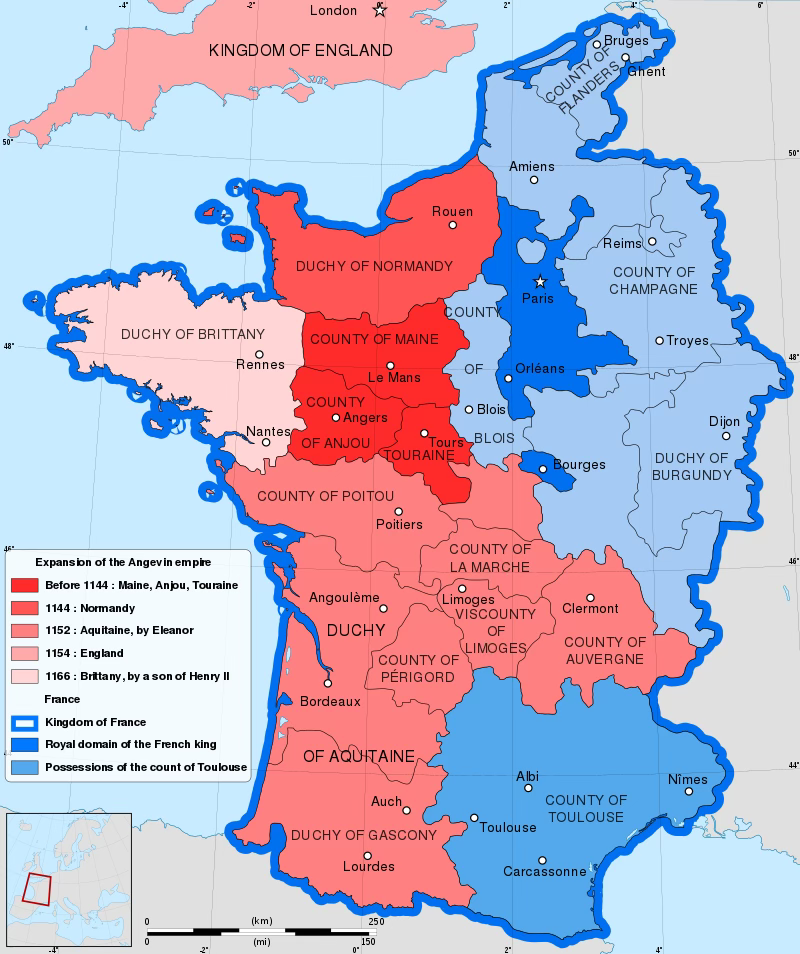

By 1148, it was clear that Matilda was not going to win the hearts and minds of the English, so she withdrew to Normandy again and planned instead to find a way to install her son, the future Henry II, on the throne. With his mother's help, Henry consolidated his power by becoming Duke of Normandy in 1151, while also inheriting Anjou, Maine, and Touraine from his father. In 1152, he married Eleanor of Aquitaine and received the duchy by jure uxoris. His marriage alliance with Eleanor effectively made him the most powerful and wealthiest nobleman in France, and far richer than the entire kingdom of England.

By the time Henry II landed in England in 1153, he had King Stephen cornered. But the English nobility, exhausted from 15 years of war, refused to fight for either of them. They gathered in what was later called The Baron’s Revolt Against War and forced Henry and Stephen to negotiate peace. By some strange coincidence (hint, hint), Stephen’s son Eustace died, and so Stephen agreed to make Henry his legal successor in the Treaty of Westminster. Stephen died the following year of a stomach issue (oh, come on, he was poisoned!), and Henry was crowned king.

All well and good, but let’s not forget that Henry was not just king of England. He was Duke of Normandy, of Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. Moreover, his titles in France made him a vassal of the French king. Did all of this make Henry a French king of England? Well, let’s do a quick thought experiment: His father was French; he was born in France and had lived most of his life there; he married a French woman; and he spoke French. How would Henry have seen himself? Trick question: he saw himself as English. That’s because we—and this was true of Henry—tend to take on our mother’s language and culture as dominant, and Matilda was not French nor Norman, but firmly English and Scottish.

Still, it’s undeniable that by the time Henry ascended the throne in 1154, his landholdings, lineage, and entourage made him look suspiciously French. Further, the king of France saw him as a definite threat within his own realm.

And this is when things got really interesting. Remember what I said about our tendency to be closer to our mother’s language and culture? Well, Henry’s wife was very French, and she raised her sons, the so-called ‘Devil’s Brood’, to be very French, and that created a lot of tension with their English father. Let’s run the same thought experiment for them: their mother was French, their father was half-French, they all spoke French, and they spent much of their lives in France (in fact, Richard spent only three months of his adult life in England). Would they have said they were French or English?

From this perspective, it appears that, for Henry and, later, his sons, England had been a mere territorial acquisition to add to their continental empire. Their main purpose or political goal, if we can call it that, was to rival the power of the king of France by gobbling up feudal estates in the French realm. We see this most poignantly in Henry’s hostile takeover of the Breton nobility. But that rivalry would lead to their undoing.

First, Henry’s succession was anything but smooth. His sons rebelled against him on several occasions, and his eldest, Henry the Younger, who was meant to succeed him, died of dysentery while on campaign in…you guessed it…France. Richard ultimately succeeded his father, but had little interest in governing. He used the English crown as a piggy bank to fund his wars in France and his infamous crusade. His was a short reign, marked by his intense self-interest and disregard for the responsibilities of leadership. When he died—from an arrow to the face while besieging the castle of an alleged former lover—the realm breathed a sigh of relief.

Richard’s death left John to inherit the Angevin Empire, but he was not spared the character defects that had earned him and his brothers the moniker, “Devil’s Brood.” Further, the empire fractured under his predecessors’ exigencies: England and Normandy backed King John, while Anjou and Maine backed his nephew, Arthur of Brittany, who was Henry II’s grandson by way of the youngest of the Brood, Geoffrey, who had been killed at a tournament in…you guessed it…France.

If you’ve followed to this point, I promise there’s a payoff—plenty of infighting, backbiting, and political intrigue to come, and it absolutely does tie back into the Hundred Years’ War.

John did the ignoble thing of killing his nephew, Arthur. No one is sure how, but the result was clear: the king of France, Phillip II, who was also related to Arthur (as a half-uncle through a half-aunt…let’s stick with ‘related’), used the murder to turn the French nobles against John. Thus began a FRENCH CIVIL WAR that ended Angevin rule. That’s right, I called it a French Civil War, because it was French on French. John was French and defending his interests in France. Phillip was French and defending his interests in France. Arthur had been French. Even John’s dog was French.

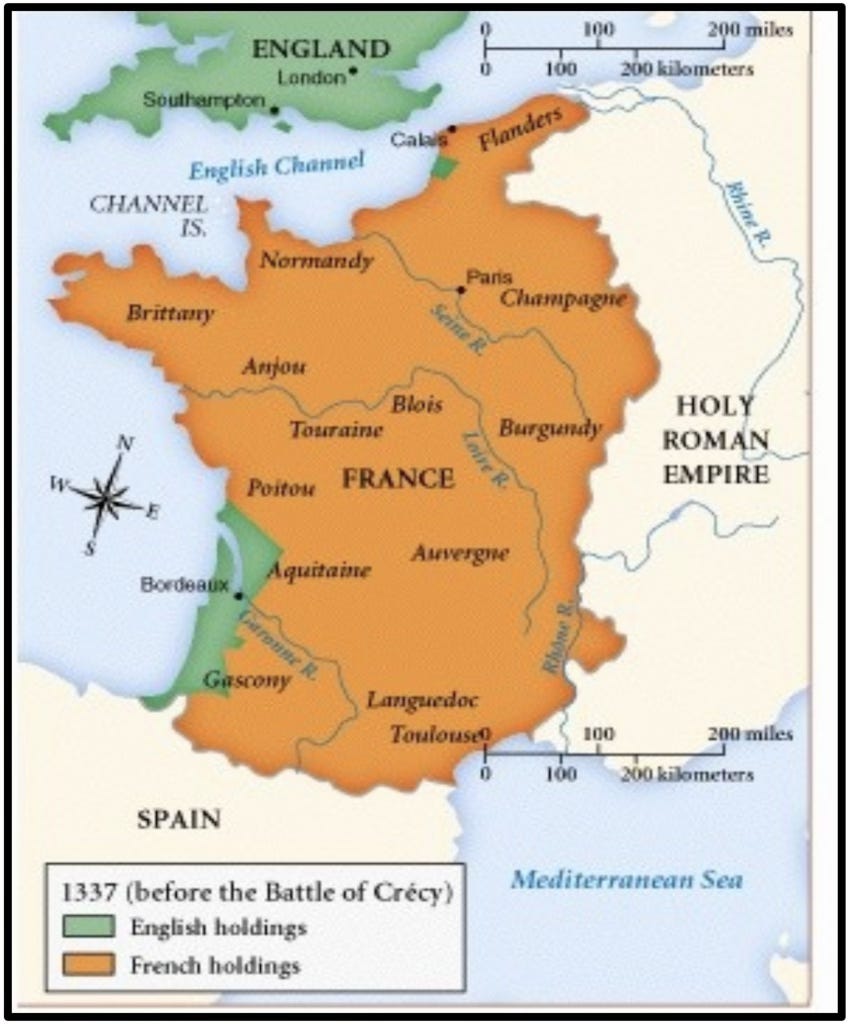

Phillip moved quickly to seize Anjou, Maine, Touraine, and Normandy. He decisively expelled John from France in 1214 at the Battle of Bouvines. By 1216, the Angevin empire had shrunk to a small “rump” state in Aquitaine.

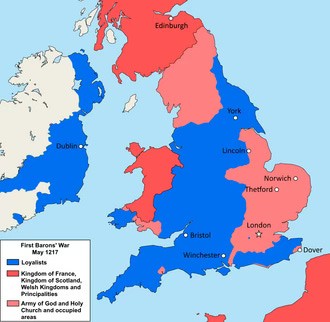

But the king of France did not stop there. This was, after all, a civil war, and he wanted to eliminate the possibility that John might gather support in France again and cause trouble. So, he launched an invasion of England. He was helped by the English Barons, who were upset by John’s disregard for the agreements he had made in the Magna Carta. You see, the English nobility had grown tired of all the French a$$holes taking control of and ruining their country, so they sought to put limits on the monarchy. When that didn’t work, they decided they might have better luck with the other French A$$hole who had just kicked their a$$hole’s a$$ at Bouvines.

Dear God… I kid you not, this is real.

Phillip sent his son, Louis, to England in 1216, and by June, he had taken London and occupied it. He and the English Barons set about divying up the kingdom while John fled…again…to…you guessed it: France.

By the way, there’s a great book about this episode in English history, Blood Cries Afar, that I highly recommend; it offers a detailed breakdown of everything that was going on at the time. My summary is just that, a summary, and hopefully one that has put a smile on your face so far.

For all intents, it appeared by 1217 that the jig was up for the Angevin line. But John threw one of history’s longest Hail Marys (for non-Americans, this is an American football euphemism for a long shot). He had, years prior, made England a vassal of the papacy, for fear of this precise situation. No sooner had Louis landed in England than he was excommunicated for attacking the papacy.

For those of you wondering: yes, that’s a 4d chess move.

John’s gambit worked. Louis’ spiritual punishment dogged his efforts to consolidate power in England. John then threw his next Hail Mary, which I am almost certain he had not planned: he died. But it was his death that allowed the barons to rally behind the young Henry III, who was, as they put it, leading a ‘crusade’ against the excommunicated French Prince. Louis signed the Treaty of Lambeth after losing the Battle of Lincoln in 1217 and returned to France.

Thus ended the first French Civil War.

The key point to retain here is that Henry III was an Angevin, albeit a much less ‘Frenchified’ one. For the next century, the French and English monarchies took two completely different approaches toward avoiding a repeat of a “French family gone wild.” The English king was constrained by his nobility and compelled to establish checks on his power, including a parliament. This was the result of England’s experience in the French Civil War, as it effectively became a hostage to a French noble family, which bankrupted the kingdom to fund its wars. The French king did the opposite. He created an overbearing administration and bureaucracy to consolidate power and curb the nobles' authority. This resulted from France’s experience in the civil war, as it had effectively lost control of one of its noble families and was drawn into the conflict. Saint Louis’ legal reforms, for example, allowed plaintiffs to go directly to the king rather than to the local noble, stripping the nobility of one of their core levers of power.

By the time we reach the 1328 succession crisis, however, we see that history has a nasty habit of rhyming, as they say today. And it didn’t start in France.

Edward II was not a nice person. Perhaps not as nasty as Mel Gibson would have us believe, but certainly not a considerate husband. When he married Isabella of France, sister to the French king, he edged her out in favor of his ‘favorite’ nobles. Isabella did not take it well. She used a diplomatic mission to France as cover to escape, and started a torrid love affair with an exiled English Baron named Roger Mortimer. By English standards, this was a scandal, but the French responded with more of an “eh…”

Isabella and Mortimer raised a mercenary army in Hainaut (modern-day Belgium) and invaded England. They were greeted as liberators by a nobility and clergy exhausted by the tyranny of the Despensers and Edward II’s failures. In a historic and legally dubious move, Isabella and her allies forced Edward II to abdicate in January 1327. This was the first time in English history that a monarch was deposed by a formal political process. Isabella and Mortimer ruled England as regents for the teenage Edward III. During this time, they enriched themselves and signed the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, which recognized Scottish independence.

So now we are faced with another English king whose mother was French (recall what I said about language and culture), who had lived a good portion of his childhood in France, and who had even attended the French court to pay homage to his uncle for his estates in Aquitaine, which made him a vassal of France. Moreover, he was still a Plantagenet.

When Charles IV died in 1328 without a male heir, the French kingdom faced a thorny situation it had been spared for well over 300 years. The “Capetian Miracle” had defied the common fate of most kingdoms of the day. And it wasn’t through any sort of competence, either. It was luck.

Still, the French state faced a succession crisis that it had no experience or laws to address. When Isabella was the first to petition the French court on her son’s behalf, they panicked. To them, it was the Angevin debaucle all over again. Luckily for them, the Captetian kings had invested heavily in an army of lawyers, or ‘Legists', to sort it all out. And sort it out they did. They resurrected an old Salic Law from long before France was even a country to justify denying passing the crown through the female line, arguing that “no woman can inherit the throne” and, crucially, that “no woman can transmit a right she does not possess” to her son.

When the newly crowned Phillip VI called for Edward to pay him homage as his vassal in 1329, Edward made a scene. He wore his English crown, carried his sword, and refused to kneel. Edward and Phillip were cousins, and they already knew each other. According to all precedents, Edward should have been crowned king of France, and Phillip knew it. But he was denied because, for all intents and purposes, he wasn’t ‘French’ enough.

I have experience with this. My father is French, and my mother is American. I speak French natively, as I do English. But I am undeniably more Americanized in culture and even language because of my mother. If I were to return to the U.S. and be denied something on the basis that I was also half-French, even though it was something I had a right to as an American, you can bet I would not take it well. And I think that’s what ate at Edward the most. In his mind (and I can’t prove this, so take it for what it is), he was French and was entitled to the French crown, but the French court denied him on the basis of his Englishness.

What we see unfold over the next few years is a chest-thumping display of two cousins locked in a deeply personal rivalry. When hostilities broke out in 1337, Edward moved with a swiftness and organization that the medieval world had not before seen. He was a man with vengeance in his heart, and one who was out to prove his ‘Frenchness’. Oddly, it took him a few years to declare himself king of France. Historians have argued that this indicates that the succession crisis was not the primary motivator for Edward’s campaigns. But to me, I believe he may have delayed doing so, hoping he might have an early opportunity to face his cousin on the battlefield and settle the matter with steel.

Like his ancestors, Henry II and the Devil’s Brood, Edward was arguably more French than he was English. In my view, the wars he led were a series of French Civil Wars that would permanently sever the two countries and give rise to two sovereign, independent nations and two separate, irreconcilable monarchies.

I’ll be teaching a ten-week course on the Hundred Years’ War here soon on Medievalists.net. If you’d like to hear the rest of the story and enjoy attacking established history from different lenses, sign up at the link below and use promo code ‘ADRIEN’ to get a discount.

Excellent!! This made for a very interesting and inquiring lecture today!

Ah, I have often thought the same. However, Edward III did much to make English the language of England and, from his spelling of French words when writing in English, his son, Edward of Woodstock (later called The Black Prince) spoke French with what appears to be a London accent ! I mean Poitiers spelt as Petters, even in English father spelt as farver and mother as muvver. I make much of the language differences in two of my novels. The first is "If You Go Down in the Woods" on the 1215-16 French invasion of England, and "The Dark Daring Deeds of Geffrey ðe Wulf", a tale of an English archer in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. https://www.amazon.com/s?k=geoff+boxell&crid=3AQOVF5RAM8X0&sprefix=%2Caps%2C301&ref=nb_sb_ss_recent_1_0_recent